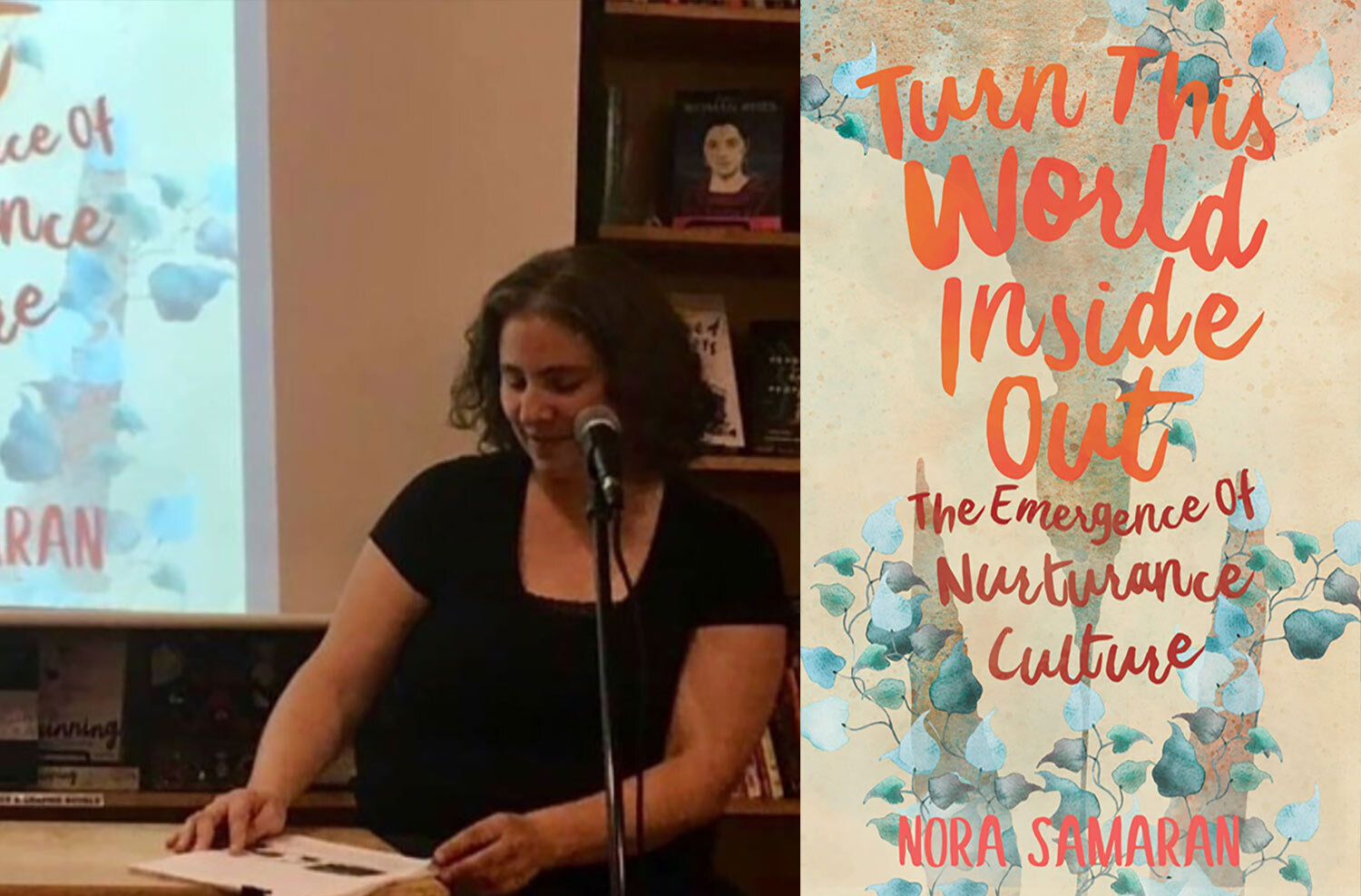

Naava Smolash is a white settler from a working class immigrant family. Her writing appears in Studies in Canadian Literature, West Coast Line, LitHub, Everyday Feminism, Briarpatch, and the University of Toronto Quarterly. Her essay “The Opposite of Rape Culture is Nurturance Culture” went viral in February 2016 and grew into a book, Turn This World Inside Out, published by AK Press in 2019. She was a member of the No One is Illegal-Vancouver collective from 2005-2009, and the Media Democracy Day-Vancouver collective from 2008-2010. Originally from Montreal, she lives in Coast Salish Territories, also known as Vancouver, British Columbia, where she teaches in the English department at Douglas College. She holds a PhD in English Literature from SFU, and is a 2018 graduate of The Writer’s Studio.

Naava Smolash is a white settler from a working class immigrant family. Her writing appears in Studies in Canadian Literature, West Coast Line, LitHub, Everyday Feminism, Briarpatch, and the University of Toronto Quarterly. Her essay “The Opposite of Rape Culture is Nurturance Culture” went viral in February 2016 and grew into a book, Turn This World Inside Out, published by AK Press in 2019. She was a member of the No One is Illegal-Vancouver collective from 2005-2009, and the Media Democracy Day-Vancouver collective from 2008-2010. Originally from Montreal, she lives in Coast Salish Territories, also known as Vancouver, British Columbia, where she teaches in the English department at Douglas College. She holds a PhD in English Literature from SFU, and is a 2018 graduate of The Writer’s Studio.

ROOM: Hi Naava! Your debut collection of essays, Turn This World Inside Out: The Emergence of Nurturance Culture, was just released recently with AK Press. First of all, CONGRATULATIONS! How does it feel to have a book out in the world?

NAAVA SMOLASH: Hi Isabella! It’s good to be here. Thanks for having me!

As for how it feels? Humbling magic. I am often surprised when we hear about where the book has travelled. I learned recently that someone put on a play about gendered violence inspired by the book in Lithuania. Someone is using it to run men’s groups in Brasil to challenge intimate partner violence. It was in an article about changing gender norms in Nigeria, and book clubs in squats in France and Spain, to name just a few. Some folks will know I wrote the essay under a pen name, Nora Samaran. A Malay speaking reader at the Oakland event observed from the overhead that one of the countries where the blog has been seeing readers is Malaysia and asked if I knew that “Nama Samaran” means “pen name” in Malay. No joke. And I had had no idea. The name happened by scrambling a few letters from my name in about five seconds, and now here was this bizarre coincidence. In other words books bring so many surprises. I’ve barely been anywhere but the book has traveled around the world.

On the other hand, my day to day life has remained very quiet and mostly unchanged. For me the book was very situated in my home communities. Bonds in my real life are what matter the most to me. I find great joy in bonds where people build trust and emotional safety in person, and feel tremendous joy when I’m able to collaborate with people I can deeply trust whose architecture of thought I also find beautiful. I’m absolutely happy the book has been meaningful for folks in other places, even while what means the most to me is meaningful collaboration and bonds in my home communities.

ROOM: Talk me through the process of how it came to be. Would you like to speak more to the essay that started this collection, “The Opposite of Rape Culture is Nurturance Culture.” This is one essay that went viral, but how did you know where to go next with regards to the overall trajectory of the book itself?

NS: I had never published a book before and the process felt very mystifying. It made a big difference that people shared knowledge, and often openly taught me things they would have found obvious, like how to speak with a publisher, or how to ask to be part of a festival.

The Nurturance essay happened during a time of isolation, and became a bridge to connection. Initially when I wrote the nurturance essay, I was trying to find my way back to a writing voice. I had lost the ability to read for a time, and I was trying to find my way back to words, to my full self. I was also trying to understand some things that had been happening to me and to people I care about, things that I couldn’t describe, which attachment theory was helping me understand. The essay combines attachment theory with cultural analysis.

As I learned about attachment, I was interested in the cultural overlay on top of the neurological experience that I realized was distorting my ability to heal. The attachment literature, like Sue Johnson’s work, tells us it “takes two to enter into the anxious-avoidant dance,” but I was noticing something else: patriarchal culture normalizes a dismissive style and stigmatizes an anxious style wherever they appear. A lot of cultural shaming of what turn out to be completely reasonable limbic needs occurs, where everyone is expected to be totally disconnected, and needing other people is somehow weak or wrong. So our culture can talk about boundary violations in one direction, but not the other. Neither of these styles are optimal, and yet our culture distorts these patterns. I wrote the piece to try to understand this.

And then the essay went viral, even as I was still in a very still and quiet place internally. The essay saw 75 000 views on the first day, and four days later it had passed 300 000 views. From the beginning the writing had a life of its own. When the book became a possibility I knew it needed to be dialogues, not one voice. My background is in race theory, and I was a community organizer for four or five years involved in migrant justice organizing. I had also been sitting in on a class at McGill taught by Rachel Zellars, a brilliant scholar of Black feminist thought and organizer. What was underneath the nurturance piece was wider thinking about systemic racism, colonization, and gender. I also knew, however, that I was not the person to speak to many of these questions that underpinned and influenced the piece, that other people could do that better than me. I had also been grappling with some harm to social fabric resulting from interactions with people who have narcissistic traits and were very power and image focussed, who were bewilderingly different in their projected image than in their private lives, who used kettle logic often, and I was very disoriented by this and writing to try to trust myself.

As a result, I wanted the book to be based not in trying to find the most “famous” or “important” people, but instead to connect with people I already trusted in day to day life because they had demonstrated trustworthiness. Embedded in the book, as you’ll see, are my interviews with Jon Snow, Serena Bhandar, Ruby Smith Díaz, Aravinda Ananda, Natalie Knight, and Alix Johnson. It matters to me to build trust with empathetic, fully ethical people who have the will and ability to protect each other and look out for one another and are not about an image. There is so much expertise in regular communities, so much knowledge that comes from people’s bodies, communities, and lived experience. That is where I wanted to have these conversations, in ways that would build safety for more of us, with empathy. The dialogues grew out of conversations that were already happening.

ROOM: What a pleasure it has been to read your book! This is a timely collection, and through which you introduce the idea of nurturance culture as integral to the ways in which a largely male-dominated, and Western society might “work to reclaim lost parts of themselves and grow their capacity to nurture others.” How might this be an alternative model—the breaking of harmful patterns, per se?

NS: Aw, I’m so glad. Thank you. That means a lot. The easiest way to answer this is to say that the title, Turn This World Inside Out, has two meanings.

One meaning is to turn a certain type of shame inside out and recognize where it come from. My father is a survivor of the nazi genocide, and he was born as a refugee when his family was on the run, hiding and experiencing really bare life; he has not done his own healing, and those pogroms, terror, and dehumanizing reach back many generations in that line. In some ways this proximity, because I’m only a first generation out from it, meant I grew up inside the energy of having been positioned as subhuman and inside the energy of having to flee the terror of mechanized, systematic genocide that had happened on another continent. My generation is now doing our best to heal intergenerational trauma. I’m also in the middle of repairing the neurological effects of gendered terror and episodic experiences of poverty and hunger during developmental years from earlier parts of my own life. And that has taught me some amazing things.

That experience of unearthing and healing internalized shame has profoundly shaped the project. So the first meaning of Turn This World Inside Out is to turn towards and recognize forms of shame inculcated or internalized by massive systems of oppression, and gently love those shamed parts, which turn out to be the most beautiful and powerful parts of the self. Through this process I came to understand what many people know: that systems of oppression turn our most beautiful parts of the self around and feed them back to us mirrored inaccurately as shameful, when those are precisely the parts of the self that have the power to transform those systems of oppression. Turning it inside out means to see that that shame never was about me, to put it back out into the world, out of my body, where it never belonged in the first place. It means to see that those places that have been masked by shame can direct us to the most powerful parts of ourselves: wholeness, where we have the power to upend systems of harm simply by existing without shrinking to fit. The contributors each speak to this in their own ways, and I’m incredibly grateful to have been able to learn from their words.

The second meaning of Turn This World Inside Out is to invert the assumption that we begin as isolated individuals, and instead begin with the knowledge of our fundamental interdependence, and then think through navigating harm with that different starting framework. Western culture conditions people to believe that we each begin as disconnected, atomized subjects. As neoliberalism is taking deeper and deeper hold, the idea that all interaction can somehow be entirely chosen has been seeping into more and more crevices in the culture. The attachment literature, meanwhile, tells us that we are biologically deeply interwoven with others; our nervous systems evolved over millennia to exist in secure, trusted bonds. Deciding that a body does not need something does not make that denial true. We could decide a body does not or should not need to drink water, but we would find out very quickly that that is not the case. The same is true, it turns out, of our need to depend on one another and to experience belonging in a limbic sense.

I began to realize that the insights of attachment theory can help us understand not only our bonds with a couple of intimates in an otherwise disconnected society, but can help us recognize our role within larger human communities and maybe even the ecological webs that literally are us, without which we do not survive. The ecological devastation we are seeing in, for instance, the Australia fires or the melting North tell us the unbearable consequences of neglecting relationality or pretending our interwoven relationships do not exist; I realized our limbic brains are already guiding us to know this is true. We have an innate gift in these exquisitely delicate nervous systems that can guide us towards a deeper perception of our belonging and balanced interdependence, in which we are connected to begin with, and are therefore responsible to meet one another’s needs both for autonomy and for connection, trust, and protection. Not only one, both, in balance.

ROOM: As you so eloquently put it in one of your podcast interviews, “we don’t have to be best friends to have solidarity.” With solidarity, comes these dialogue exchanges, but you’ve also continued to build conversations, in an ever-widening expansion of circles since the publication of your book. Would you like to talk more about some of the podcasts you’ve been on, events, and circle discussions among kin?

NS: I had the experience that I have heard described as screaming into the void, where you clearly speak up about harm that is happening to you, but your words have no meaning to the people around you, not because the harm is not blatant because the harm is so naturalized it is rendered hard to perceive. People may have no schema or framework for recognizing what your words mean, even when you’re being concrete. People around me had to do very deep listening to overcome their own conditioning not to recognize harm even as it happened right in front of them. Through this experience, I had come to understand that I really wanted to understand the types of harms others face that I might not be able to immediately recognize myself. I learned how deeply we must listen to one another to grow understanding of how systemic harm functions in people’s lives. This is an iterative practice, where we only understand a little at first, and then with listening and coming back we can come to recognize more over time.

The contributors I interviewed in the book each drew on their own experiences and insight into what turning shame imposed by systemic violence inside out meant for them. I feel immensely grateful for the gift of their insights. It seems to me that that kind of teaching is an immense gift to give because it comes at a cost. Speaking these truths can risk the terror of that reality being obliterated again, of deep cognitive or bodily erasure. And yet at the same time, to be able to build solidarity in this way, to come to know what it would look like to protect one another, is the main way I find strength and hope. We need to depend on each other to know that we can organize and resist, and that takes a capacity to do very deep listening.

The book project grew in a very relational way, and so perhaps unsurprisingly the gatherings have happened in the same way. My favourite events have been organic where relationships of trust are being cultivated, like a small circle that Jónína Kirton organized in her home, which was moving because I was able to listen and share in a very safe accepting container held by that circle, or the Surrey Muse gathering organized at the Surrey Public Library by novelist and poet Fauzia Rafique. Memorable moments of this kind where I’ve been kind of pinching myself have been book events with people I love and admire who had been my professors. For instance David Chariandy generously moderated the opening Vancouver launch with Ruby, Serena, and Aravinda, which meant so much to me and to the contributors. At the Calgary launch, Larissa Lai posed such thoughtful incisive questions that shaped the conversations for the rest of the book tour. It has meant more than I can express to be able to share space with people I have respected over many years in this way. I also feel immense gratitude because events like these were helped and supported by people who put in hours of time and effort behind the scenes creating space in ways I would not have known how to do, such as Jennifer Andrews at ACCUTE, Laura Moss at UBC, or Kit Dobson at Mount Royal U, whose encouragement and care work organizing makes so much possible for someone like me who is not naturally familiar or comfortable navigating academic space or literary communities. I hope to share that care work and build room for others with space I’ve been given now.

I loved Dena Rod’s review in Argot magazine, which also felt like a relational conversation because it got the book so well. The Healing Justice podcast and practice was another space, where community is being woven in and around the book in a way that I’m very grateful for. Often after each podcast I leave feeling that was the best one, my favourite! Because the conversations can get vulnerable and vary based on what arises with each person. Some of the ones where I felt we went in surprising directions, or crystallized ideas together, were Dawn Serra’s Sex Gets Real podcast, the Final Straw, or Laborwave.

ROOM: So much is on the horizon. I love how in each of your dialogue exchanges, the conversation seems to always end with hope, looking to the future. Tell me, what’s next for you? By that, I’m asking in terms of growing out of this project—how might we continue to build solidarity, and discussions centered around nurturance and care? Also, what are you most looking forward to, outside of writing?

NS: The book was really part of a bigger project! The other half is a speculative fiction novel. It came fully formed as a whole cinematic dream with credits and title rolling at the end. I workshopped the manuscript last year with The Writer’s Studio at SFU in Hiromi Goto’s speculative fiction mentor group. I understand more about what the structure and characters in the manuscript need and am revising. Getting it ready and finding it an appropriate publisher is the next project.

And I’m also very, very tired. So I’m looking forward to summer, and to getting out to a lake in July and doing absolutely nothing but hiking and swimming with close friends for a while.