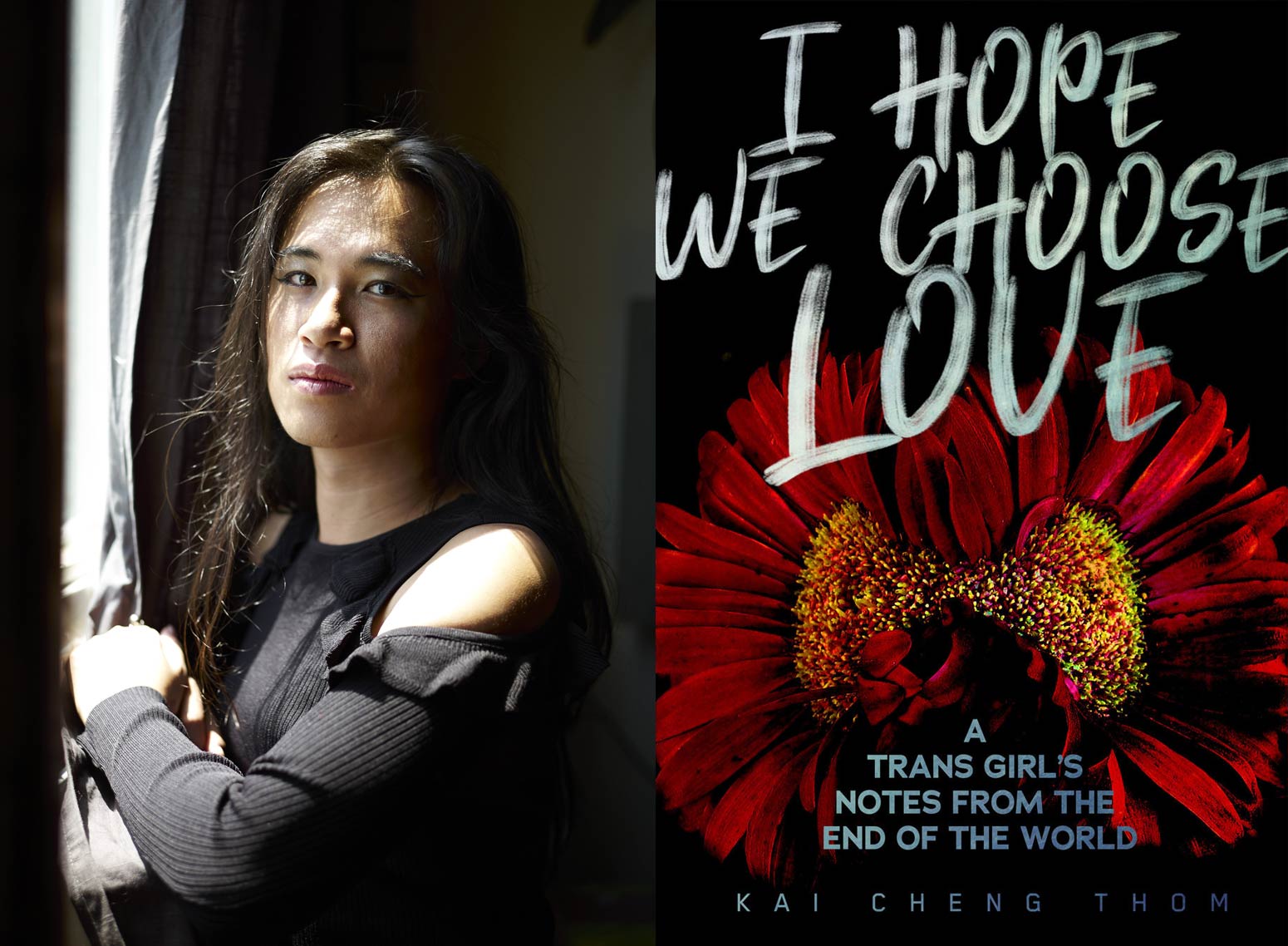

Kai Cheng Thom’s latest book, I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes From the End of the World (Arsenal Pulp, 2019), is an expansive and intimate collection of essays and poetry on transformative justice and radical love, both in and beyond queer activist communities. Read what the multi-genre writer thinks about choosing love, writing in different genres, and the ideal secret society.

To celebrate the upcoming Growing Room Festival 2020, we are chatting with a few festival authors to learn more about them and their work until March rolls around. Stay tuned for more conversations in this interview series. In the following interview, Rebecca Salazar (Room contributor, contest winner, and Growing Room writer), chats with Kai Cheng Thom who will be the keynote speaker at this year’s festival!

Kai Cheng Thom’s latest book, I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes From the End of the World (Arsenal Pulp, 2019), is an expansive and intimate collection of essays and poetry on transformative justice and radical love, both in and beyond queer activist communities. Read what the multi-genre writer thinks about choosing love, writing in different genres, and the ideal secret society.

This interview was conducted over email.

ROOM: Congratulations on the recent publication of I Hope We Choose Love. In the past four years you have published books in multiple genres—poetry, children’s books, and “confabulous memoir.” Do you choose to work in a particular genre when starting a new project, or do you feel like the genre or story chooses for you?

Kai Cheng Thom: I think that each particular story demands to be told in a particular genre—and some stories demand multi-genre or hybrid genre in order to reach their full expression. As a trans, East Asian, diasporic woman, I often feel the same way! I think most of us who struggle to live within colonization and capitalism are in fact creatures of many kinds of story.

I should also say that, as a writer, I am very deeply influenced by multi-genre artists and innovators. Maxine Hong Kingston, Audre Lorde, and Ntozake Shange in particular are writers whose work in magical realist memoir, biomythography, and choreopoem respectively shaped my sense of what writing and storytelling can do in the world.

ROOM: I am struck by the subtitle of I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes from the End of the World. It echoes the title of the advice column you pen for Xtra, “Ask Kai: advice for the apocalypse.” Do you feel a connection between these two bodies of writing, and if so, how are they linked?

KCT: I’m so glad you noticed! My advice column and I Hope We Choose Love are definitely linked—the column was conceived that way, in fact, in collaboration with the fabulous Xtra editorial team. Both bodies of work share the foundational perspective that we are living in a time of enormous crisis, and that the only workable political ethos in such a time is one based in radical love.

ROOM: The sense that the world—at least as we know it—is coming to some impending doom is something I have noticed is a fixation for many younger writers, including myself. Why do you feel your work is called to address apocalypse and the grief that comes with it?

KCT: I have always believed that storytelling must come from a place of political urgency—that writers and artists are ethically compelled to respond in some way to the world around us, even when we are creating from a place of fantasy or abstraction. It is our job to tell the truth as we understand it, to speak for and with those around us, to bring both beauty and discomfort into the collective consciousness. And so I write about “apocalypse,” both literally and as metaphor, because I truly believe that the world as we know it is ending. Climate change, capitalism, colonial society—all of these systems are going through enormous shifts that will bring both destruction and the potential for growth. Writing and talking about it helps us to understand what is happening, to process the inevitable losses, and to plan for survival and rebuilding.

ROOM: The essays in IHWCL range in scale—between dealing with climate change, activist communities fractured by conflict, and the daily violence faced by trans women. Your writing always steers away from immobilizing responses like anger or despair, though still affirming that these are valid responses to loss whether on a collective or individual scale. Instead, care work is the response you propose to cope with harm, and “I hope we choose love” becomes almost a refrain throughout the collection. How do you define that kind of love and the work it entails?

KCT: “Choose love” has definitely become an informal mantra of mine over the past couple years—if only because my friends say it ironically around me all the time now! I would actually push back a bit on this question, though, because I don’t think that I do steer away from anger or despair as such. Anger and despair are natural, vital human responses to a society that is exploitative and violent. And I think that part of choosing love is affirming those emotions that are often stigmatized as “negative” or “toxic,” because all emotions have a place in the human spirit. What I do advocate against are politics based on revenge and disposability.

It’s interesting to frame choosing love as a kind of care work because that isn’t necessarily the way that I always think about it. I like that, though, because I think what a lot of people miss about I Hope We Choose Love is that it is first and foremost a book about choosing to love yourself—which is a huge piece of work for most of us! To me, radical love is the act of choosing to see all human life as sacred, which includes one’s own life. It’s about refusing to compromise, refusing to accept political solutions that deem some people (ie, marginalized individuals) an acceptable loss as part of a larger project of supposed safety or freedom.

In practice, this can look like any number of things, but one example that feels particularly relevant is the notion of justice: most mainstream, contemporary understandings of justice are based on the binary of victim/offender or survivor/perpetrator. In order for justice to be done, someone must be punished, incarcerated, killed, or otherwise gotten rid of. In contrast, choosing love could look like transformative justice, which is about holding the broader community accountable for its participation in creating the conditions that lead to violence, creating healing for all those involved, and changing society so that violence can never happen again.

ROOM: A lot of your writing—I’m thinking here especially of Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars—suggests that storytelling is one of the most accessible and life-giving resources we have. For LGBTQ+ folk and people of colour especially, writing our own stories is the only way to create a future we can see ourselves surviving in. What do you think makes stories so transformative?

KCT: Storytelling is the essential act of bringing human dreams into the waking world. It is the embodiment of the human impulse to create, to communicate, to connect and transform. I truly believe that storytelling and art-making are a human right and one that has been denied to LGBTQ people, people of colour, and other marginalized individuals throughout much of modern history. Colonial oppressors literally outlawed the telling of Indigenous, POC, and LBTQ+ stories for many, many years in an attempt to erase us. This is why storytelling is such a powerful and important aspect of liberation movements (though it cannot be the only aspect that we focus on!). It is an act of spiritual and cultural reclamation.

ROOM: If there are one or two books you’ve read in the past decade that most help you imagine new possible futures, which books would those be?

KCT: This is so hard! There are so, so many books that I love. But if I had to boil it down to two right now, I would choose: Wild Seed by Octavia Butler and Sub Rosa by Amber Dawn.

ROOM: Lastly—and this is a speculative question—what are your wildest dreams for this year’s edition of Growing Room? These can be small hopes or large ones, from starting a CanLit revolution to finding the perfect vegan donut.

KCT:

- We start a Secret Society of Revolutionary Poet-Swordswomen for the liberation of all peoples.

- We take all the money from fancy elitist CanLit institutions and use it to start art and storytelling centres (with free dinner!) for poor and marginalized communities

- We all decide to take a break from self-shaming and cancel culture and be kind to ourselves and one another instead.

You can join Kai Cheng Thom at the following Growing Room Literary & Arts Festival 2020 events on March 14 and 15:

Self-Love and Community Care: Ethics of Community Building (Panel)

Transcending the Narrative: Trans Women & Surthrivance (Reading)