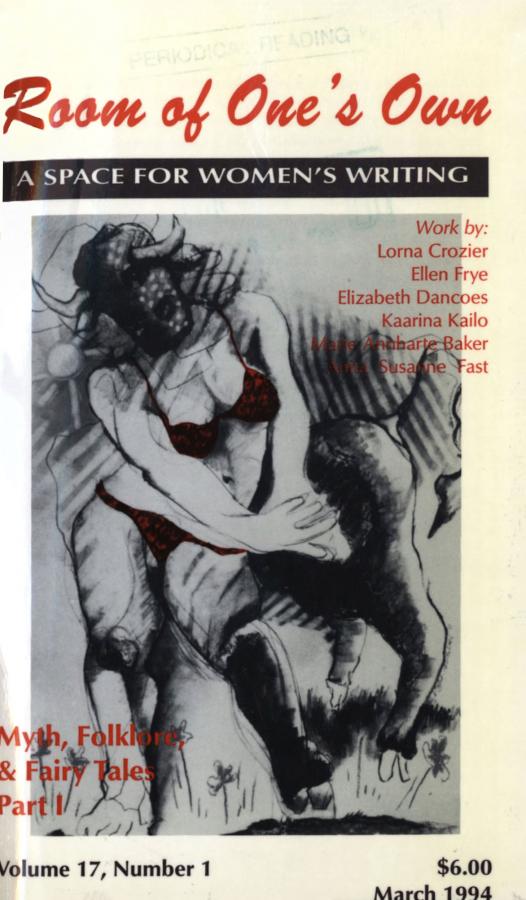

Myth, Folklore and Fairy Tales Part I | 17.1

1994

Digital only; out of stock in print.

My first exposure to analysis of fairy tales was through a pop psychology book I read in the mid-1970s. The author argued that Little Red Riding Hood was a behaviour model for girls, and women who bought red coats-particularly hooded ones-were prone to related behaviour patterns. Because they act on subconscious cues, the author claimed, these women were more likely to be victimized. Being young and naive, it did not occur to me to examine his analysis further. Instead, after purging my wardrobe of the colour red, I became obsessed with watching women in red coats, trying to detect this fatal “character flaw.”

Twenty years later, I am still fascinated by the messages filtered to our collective subconscious through traditional tales. These stories have a tremendous impact on the way we, as women, are trained to perceive the world. The way we leam to speak—by listening, mimicking, and setting down communication patterns in our minds, so do we absorb the constructions prescribing gender- assigned roles and proscribing social scripts at a highly impressionable stage of our development. The structures of traditional tales are reinforced all around us, from the paradigms of religion to the hierarchies of business to popular culture.

There has been a fair amount of research done in the area of feminist analysis of traditional tales—particularly fairy tales, though much of it focuses on a psychoanalytic approach. While this reflects a value for social individualism, examining tales through the filters of other disciplines yields alternate interpretations.

Perhaps the most popular tale in North American popular entertainment is Cinderella. From pictures book versions for (girl) children to films like Pretty Woman and “women’s” magazines like True Romance, we are presented with a model for obedience and dependency, waiting for our prince to come. This interpretation is only one step away from waiting for redemption by our saviour. Margaret Starbird, in her book The Woman with the Alabaster Jar (Bear & Company, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1993), links the symbols of Cinderella to the doctrine of heretical Christians before they were sent into hiding by the Roman Catholic church. According to Starbird, Cinderella represents Mary Magdalene—not as a prostitute, but as the bride ofJesus who goes into exile alter his crucifixion— whose true position in Christianity is thwarted by the wicked step family, the Roman Catholic church. Nature—the cosmos as under stood by astrologers—in the form of mice and birds, aid Cinderella to fulfil her destiny as bride of the bachelor prince, Jesus, healing the wasteland of patriarchy by balancing male energy with a feminine counterpart.

How we read symbolism of traditional tales defines, then reinforces, the canon that sets standards by which cultures operate. While European tales comes to mind easily, it is also a disservice to ignore the vast range of tales that comprise the background for other cultures. Understanding the paradigms presented in folk tales is to understand cultural attitudes and social values. Just as Kaarina Kailo explains how the princess of western fairy tales prescribes passive behaviour for women, Marie Annehart Baker’s explanation about storytelling with coyotisma provides a model where women are expected to be active and take part in creation. Baker says that “Ojibwe stories of creation have centred on stories of a flood which probably goes back to the ice age. Some have adapted the stories to fit the Noah in the ark Bible story. Nanabush, the Trickster, is the prime agent in re-creating the world when the waters cover the land. … The stories of two women adventurers seemed to spread throughout North America.”

In this collection of stories, the authors seek out alternative models, be there visions be redemptive—like Karen Phillips ’“Sarai,” or liberatory—like Elizabeth Dancoes’ alternative to the Judeo-Christian creation myth, a complete re-visioning of the creation of the constellations.

As a child, I protected myself by “forgetting” the endings to tales I didn’t like. Needless to say, there were very few endings I remembered. Perhaps this collection of tales will make its way to girls across the country, who will no longer have to forget the script in order to live with it.

—Wendy Putman

$10.00

Additional information

| Delivery | Canada, USA, International, Digital |

|---|

In this issue: Kelley Aitken, Marie Annharte Baker, Jennifer Boire, Melissa Branicky, Diane Collet-Laricheliere, Lorna Crozier, Elizabeth Dancoes, Marnie Duff, Anita Susanne Fast, Ellen Frye, Zaffi Gousopoulos, Elizabeth Greene, Virginia Lee Hines, Kaarina Kailo, Joanna Kafarowski, Joanne Mackenzie, Debora Meltz, Karen Phillips, Wendy Putman, Heidi Reitmaier, Gretchen Sankey, Tamara Steinborn