Ricepaper Magazine has been publishing literature and art by Asian Canadians since 1994. Though they transitioned to digital only in 2016, Ricepaper is currently running a Kickstarter campaign for a print anthology, Currents. We spoke to Ricepaper’s fiction editor Karla Comanda and poetry editor Yilin Wang (also a Room collective member!) about the campaign, and changes to their magazine over the years.

Ricepaper Magazine has been publishing literature and art by Asian Canadians since 1994. Though they transitioned to digital only in 2016, Ricepaper is currently running a Kickstarter campaign for a print anthology, Currents. We spoke to Ricepaper’s fiction editor Karla Comanda and poetry editor Yilin Wang (also a Room collective member!) about the campaign, and changes to their magazine over the years.

ROOM: Ricepaper is returning to print as an anthology. Can you tell me about Currents, and the Kickstarter campaign to help fund this project?

KC: I’m very humbled by the support that people have given us with this project.

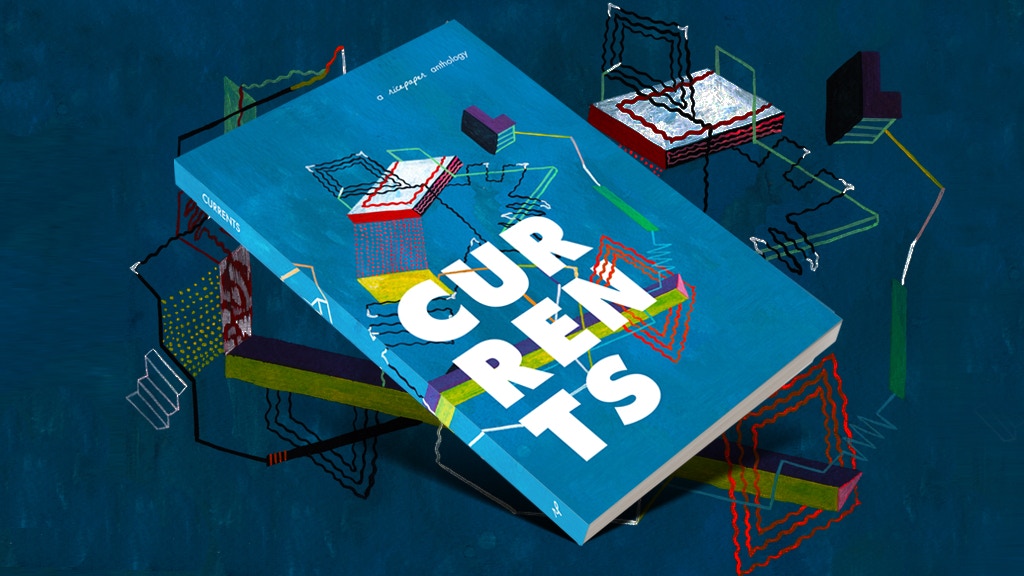

Currents will be our first print anthology since we transitioned into a digital magazine in 2016. We selected twenty-five of the best pieces we published, each reflecting a different fibre of the Asian identity.

Since Ricepaper is volunteer-run, it was quite challenging to get this project off the ground. This is where we turn to the community for support. I feel that the anthology is our way of giving back to the community. Our writers wrote their narratives; now they have to be read. I believe that the current political and cultural climate makes their stories all the more important. We certainly owe it to the writers to be heard, and this anthology is another medium where we can reach our audience.

Also, a book is a book. You can feel the spine, run your fingers through the words, read a poem on the bus—it’s not something you can replicate digitally, and with the anthology, readers interact differently with the book.

YW: I used to work for Ricepaper’s editorial team when it was still a print magazine, and recently I was invited to rejoin the Ricepaper team. When I rejoined, Karla, our fiction editor, and William Tham, our creative non-fiction editor, had already finished selecting the pieces for Currents, so I wasn’t involved in the process of putting it together. They did an amazing job and I’m really glad to see the best pieces featured online this past year compiled into a beautiful book. We plan to have the anthology as a biannual publication. Our Kickstarter was recently named one of Kickstarter’s “Projects We Love.” Please consider supporting our campaign and share it widely.

ROOM: Aside from going from print to digital, how has the editorial direction of the magazine evolved over the years?

YW: When I first started helping out with the print magazine about three years ago, the magazine was very focused on publishing the best work of Pacific Rim Asian Canadian writers, both emerging and established. We were also limited to publishing mostly Canadian content because we were relying heavily on grants from arts councils in Canada back then.

Now that we’re online only (except for the anthology), we are going back to our earliest roots and focusing on helping to nurture emerging Asian Canadian writers. I’ve also been having conversations with our executive editor and team about increasing diversity—I hope to start an equity committee to work towards supporting and featuring more Asian Canadian writers who belong to other underrepresented groups, whether in terms of gender, sexuality, class, geography, physical ability, or genre.

KC: To further Yilin’s point, what excites me the most about the transition from print to digital is the amount of space that we have now. I’m sure that with Room, you are probably aware of the challenges of print—pages, authors, content. I think that our digital platform really gives us a lot of freedom to publish more work from more people of different backgrounds.

Our staff members have been working really hard on reaching out to different groups of people—in the past few months, we have published writers from Hong Kong, China, and Malaysia, some of them in translation. It’s really cool to see what contemporary writers from other parts of the world are writing about, and to see their styles, their influences.

I think that this shift has also allowed us to work more closely with the writers, especially emerging ones. It’s an exciting process to see their work change from a draft to a published one. It’s amazing what stories they bring to the table.

ROOM: As you said, Ricepaper publishes work from not only Asian Canadian writers but Asian writers from around the world. The terms “Asian Canadian” and “Asia” encompass a disparate group of cultures and identities. In your view, what connects Asian Canadian/Asian writers and why is it a useful or important for writers identified as such to coalesce?

YW: For as long as I have been involved with Ricepaper, we have had discussions about what is considered “Asian.” It can be a really difficult and problematic term to define, because there are often discussions about which countries form Asia, and some people prefer not to be labeled as Asian. Recently I met an Indo-Canadian writer who admitted to me about not being sure whether she could submit to Ricepaper because she wasn’t sure if she is “the right type of Asian.” I encouraged her to submit anyways. Traditionally, we have mostly published writers from East Asia. I’d love to feature more Asian Canadian writers from other regions in Asia—like Southeast Asia and South Asia—as well as Asian writers from across the diaspora.

Asian writers who live in countries where they are the majority often have a very different experience compared to those who live in countries where they are a minority—and their work can reflect that. It’s important to feature their work together and have discussions, and at the same time to go beyond that—writers of colour, especially those who are minorities where they live, often feel the pressure to have to write about or represent their culture in their work, which can be a big challenge and very stifling.

KC: Even when I joined Ricepaper last year, we still had discussions about who is Asian Canadian and what it means to be one. Geographically, Asia is really broad, and when you take in who belongs to that definition and what it means here in North America . . . it’s hard to pin down, because everyone is from a certain background and our experiences are so different.

I completely agree with what Yilin said—no matter what part of Asia a certain writer identifies with, I would encourage them to submit. We need writers of colour now more than ever.

ROOM: We were sorry hear about the passing of your founder, Jim Wong-Chu. Please tell us about how Jim shaped Ricepaper over the years, and how you hope to continue his legacy.

YW: As one of the founders of the Asian Canadian Writers’ Workshop (ACWW), which first launched Ricepaper in a newsletter format, Jim Wong-Chu’s impact on Asian Canadian literature and the Asian Canadian community is enormous and impossible to convey in a few lines.

He really paved the way for the start of the Asian Canadian literary scene: he published the earliest anthologies of Asian Canadian writing, wrote the first book of poetry by an Asian Canadian writer, and inspired and mentored many of the well-known and emerging Asian Canadian writers whose work are being published today. He directly shaped and continues to inspire the work that we do at Ricepaper—our mission to find, encourage and publish up-and-coming writers who might not otherwise be heard.

On a personal note, my first poem published in a Canadian literary magazine was accepted by Jim Wong-Chu when he was co-editing Ricepaper’s Asian-Aboriginal collaborative issue. He really encouraged me when I started out, and I probably wouldn’t be involved in Ricepaper if not for him.

KC: Jim Wong-Chu was instrumental in shaping Asian Canadian literature. He worked tirelessly to advocate for the community, and he really helped plant the seeds for the ACWW, Ricepaper, and LiterAsian (his most recent project). He was involved up until the very end. We had a meeting about LiterAsian recently with the ACWW, and someone made a light-hearted comment about needing a few people to do what Jim has done in the past. It’s really up to us to grow it.

On Yilin’s point about him publishing anthologies on Asian Canadian writing—I can’t even imagine how important the anthologies he helped publish at the time were. His hard work really paved the way for us in the writing community. With Ricepaper and Currents, I hope that we can continue to honour his legacy of nurturing emerging Asian Canadian writers.

ROOM: I understand you’re expanding the LiterAsian festival. What can we expect from this year’s programming?

YW: LiterAsian, our annual festival, is happening this year from September 21 to 24 in Vancouver. The theme this year is Storytelling & The Art of the Novel. We’ll be having a range of exciting events: our anthology launch, book launches by festival authors, the announcement of the Jim Wong-Chu Emerging Writers’ Award, author panels, and writing workshops. Eight authors are featured: Eleanor Guerrero-Campbell, Catherine Hernandez, Leslie Shimotakahara, Terry Watada, Jen Sookfong Lee, Janie Chang, Leanne Dunic, and Julia Lin.

We’re also hoping to start organizing some events in Toronto around the same time, and the details for those will be shared on our website and social media once finalized.

ROOM: We are living through a moment of openly white supremacist rhetoric spewing from the White House. How do you see the role of art and literature in combatting racist systems and attitudes?

YW: It’s been quite stressful and traumatizing to follow all that has been happening in the United States in terms of white supremacy, racism, and the oppression of many groups. As I delve more and more into social justice issues, I become increasingly aware that racism and racial issues are not only present with certain extremist groups, but also can be very much present in systematic oppression and in daily life, including in writing communities. However, I hold onto the belief that literature and art are very powerful—they have the power to help underrepresented voices get heard and to help others consider different perspectives. Understanding is a crucial first step to any type of change.

KC: I feel that people still underestimate the impact of art and literature to fight different systems of oppression. It’s been said time and again, but the personal is political, and vice-versa.

To speak more personally, I’m a part of the UBC Philippine Studies Series, which is a network of Filipino students at UBC. Last year, a friend of mine and I collaborated on an adaptation/parody of the Catholic Prayer for Souls, which our group performed in protest of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos’ military burial. Soon after, different groups in Vancouver, Toronto, and Berlin also performed our work. It was so empowering and moving to know that other people were inspired by our work that they have incorporated it into their own protests.

The interesting thing for me is that I didn’t feel like the art belonged to me—it belonged to the community. It was a consequence of the community’s collective anger, sadness, and passion.

All this to say that ultimately, I think that art is a vessel of protest that people can articulate themselves with, whether it’s through their own work or others’. The internet and social media have really changed the landscape of how art is produced and received, and I am looking forward to the many possibilities of art disrupting these systems of oppression.

ROOM: Do you have any advice for writers who want to submit to Ricepaper?

YW: As the poetry editor, I’m very open to and excited to read a wide range of voices and styles, ranging from the traditional to the avant-garde. I really appreciate writers who have a way with language, and I love to see creative and unique takes on our themes, whether in terms of content or form. I have a special fondness for well-written poetry in the speculative genre (such as fantasy, science fiction, or magical realism), so send me your genre pieces that might not fit other poetry magazines with a more “literary” style. Also, I sometimes collaborate with our translations editor, Nick, and I’m open to considering high-quality translations of poetry written in other languages by Asian writers. The poetry featured in our new Celebrate issue will be posted online by early or mid-September, so you can check our website to read what I recently accepted.

KC: I enjoy writing that takes risks with form and content. But above all, I want to read stories. Everyone has a narrative that only they are capable of telling. As I mentioned earlier, it’s been really cool to see what the writers we published have brought to the table in terms of perspectives, influences, and backgrounds. Write what you would like to read about.

As a writer myself, I struggled with what I considered to be my best work, holding it up against white standards—standards that have historically invalidated the experiences and styles of writers of colour. Don’t be afraid to take risks and make your voice heard.