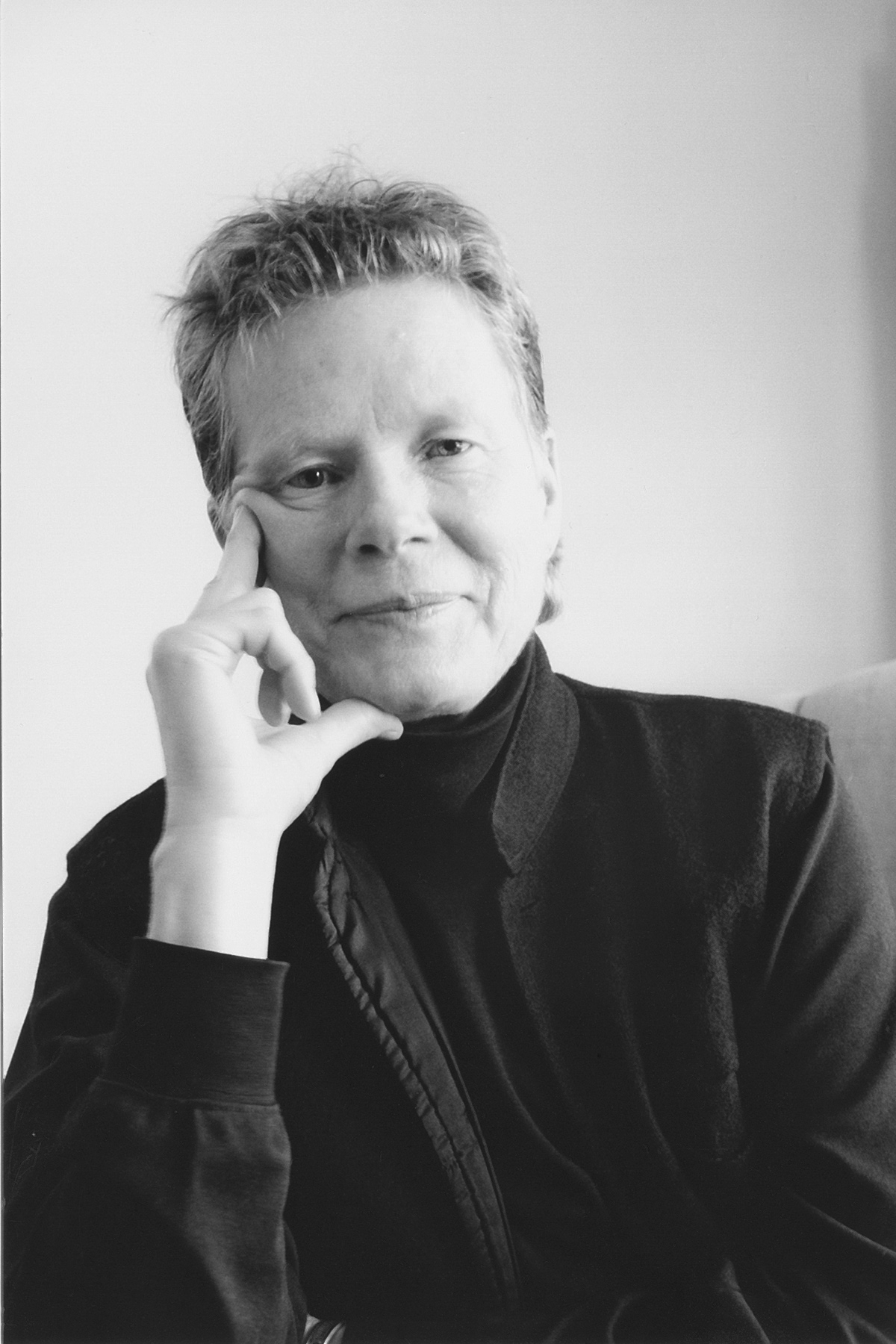

Jónína Kirton in conversation with Betsy Warland, from issue 39:4 “This Body’s Map.”

For this interview I met with Betsy in her home. We are steps away from Stanley Park, surrounded by trees. Her home, like her writing, is uncluttered yet warm. No “walls of words” or homes filled with the unnecessary for this contemplative soul. With Betsy, every word, every visual cue, and every movement—intentional; self-contained yet open and responsive. Like many long-time meditators, she has mastered the art of sacred witnessing. An ally to many, she has been a safe place to land for her readers and for all those she mentors.

Despite all this, I am nervous and uncertain about how to proceed. Betsy has been a beloved mentor and dear friend for nearly ten years. Given this, I feel an added pressure about this particular interview. How to do her and her work justice in this short time had been on my mind for the month leading up to the interview. But as always, Betsy knew just what to do. She had asked me to bring my laptop. When I arrived, she suggested we not talk, that we sit across from one another and just write back and forth on a shared document. Throughout the conversation there were moments that I was tempted to speak. Barely a word would escape my mouth before she would playfully put her index finger on her lips and a very quiet shush sound would be offered as she pointed to the laptop. There were many giggles throughout. Some noted here.

As we shared, a theme arose.

“To note each other accurately; be noted accurately: what we long for.”

—Betsy Warland, Oscar of Between: A Memoir of Identity and Ideas

Betsy’s book explores the many ways we intentionally and unintentionally use camouflage to negotiate the world we live in and how the use of camouflage affects the chances of being “noted accurately” especially for those of us who feel “between”. The noting of this longing in herself and others has informed Betsy’s writing and her work with the literary community.

ROOM: Your most recent book, Oscar of Between: A Memoir of Identity and Ideas, was released in Spring 2016. For several years now parts of this book have been posted as excerpts on your website where you ask others to respond to what you and your guest authors write. Interactive and impactful, these offerings often reflected on camouflage. How did you to come to the theme of camouflage, and was it a major revelation, or something that you were previously aware of?

BW: Like most of my writing, it came to me. I’d just arrived in London and was reading Time Out mag for what was going on and this [exhibit] literally jumped off the page. Normally, going to a place like the Imperial War Museum is the last place I’d visit, but I knew I had to see this exhibit for some reason and, once inside, within the first minute or two I suddenly had the revelation that I’d never been taught the social skill of camouflage that’s so essential to fitting in and creating automatic acceptance.

ROOM: In your book we find that there was another writer in the family, an uncle. We learn that in a sense he and his work was excised from the family narrative. You revisit the story of how your mother wanted to cut out pages from your first book. Both appear to be pivotal moments. To quote you: “. . . [she] comprehends her parents’ distrust of books. Books can: kill.”

This is such a powerful statement. It speaks to the fear of disclosure that exists in so many families and this fear is something that we as writers must work with.

BW: These kinds of pivotal, powerful moments when the veil (camo) is lifted are often the ones we rush by and quickly “forget” or feel it’s taboo to acknowledge publicly and I think this causes unfathomable suffering.

ROOM: So much of what you do for others is to ease some of the suffering. You have a keen awareness that writers need support. Did you have this in mind when you designed the Simon Fraser University’s Writer’s Studio (TWS)? Was it an effort to create an inclusive writing community from the beginning or did this reveal itself as the studio progressed?

BW: I have felt on the outside since being a very young child, for a number of reasons which I won’t go into right now. As an adult, I was more interested and attracted to other outsiders; not particularly similar to my kind of outsiderness. I designed TWS based on the desire to not only welcome diversity but to foster it. Also, I’ve seldom fit into established literary groups and organizations, so over the course of my writing life I’ve consistently been involved in creating other forums for writers beginning in Toronto with The Women’s Writing Collective in the seventies, to Women and Words/Les femmes et les mots (one thousand women from across the country) in Vancouver in the early eighties, to TWS. Being an outsider inspired me to create new options for myself as well as others.

ROOM: As a mother I have given my son what I did not get as a child. Much to my surprise this brought great healing to me. Have you found this with your work in the literary community? Did giving others what you may not have had bring you some comfort?

BW: Absolutely! And, like you, this is true with my son for me as well.

ROOM: In Oscar of Between we learn more about Betsy as a mother. I found the shared moments with your son so very tender and touching. [Jónína is shaking her head and saying with heartfelt emotion “I was so struck.”]

BW: I dedicated Breathing the Page—Reading the Act of Writing to my son “. . . who is one of my best and most fascinating teachers.” He was surprised as he’d never thought of himself in that way and asked me what I meant by it. When I described why, there was this great smile on his face: he got it. It’s tricky writing about our children.

Decades ago, at a women writers’ conference I co-edited the conference proceedings. One of the panels was focused on being a writer and mother. A couple of the writers I edited left out so much of the good, funny, and challenging stuff about juggling being a mother and writer. When I asked them why they had deleted that stuff they acknowledged that they were uncomfortable, even a bit afraid, that there might be repercussions: that it could put them at risk as mothers. It really stunned me.

But years later, I have had to struggle with how to navigate this myself. Mothering is so core to our lives yet it can make us vulnerable in some pretty profound ways. In Oscar of Between I’ve begun to find a way to honour this at least a bit. I think we’re still limiting ourselves a great deal in terms of writing freely about this “subject matter”.

ROOM: And how we define “mother” is also an issue. I have raised my nephew since he was orphaned at fourteen and he is now dealing with cancer. I have to insert myself into his care, to justify my place as his “mother.” I recently tried to write of this and these lines came to me:

and I afraid of loss love you anyway

some of us are born mothers

heat seeking missiles

we find daughters in restaurants

nephews who become sons

our own son not enough

we need more to love

As an Indigenous woman this also goes back to community and how we view family. In my culture we care for more than just our own children or blood relatives. The daughter I speak of above is not my biological daughter but a young First Nations woman that I met shortly after she was released from foster care. I could see that she needed a ‘mother’ presence in her life. I feel this is true of you, Betsy. You see this kind of need in others.

In some regards, we are all your children (meaning those you have mentored). How do you feel about that?

BW: I’m wordless! (long pause!) What I have been aware of from very early on in my life is that I am here, in this life, to support others. This matters to me more than anything. I feel we are given our stories as writers and that it’s crucial we surrender to them and write them with our utmost skill and heart. This is the source of everything. So, this is what mothering other writers is about for me. I’ve never used that term for myself but what I do say is working deeply with another writer on her or his writing is a form of soul work. Their entrustment means a lot to me.

ROOM: This may be a tangent but I do find it curious that using the term “mothering” could be seen as patronizing or diminishing of those in need of this. Yet I do feel that there are times in life when we are all in need of a little “mothering” and certainly when one takes the courageous step to write, mentorship is so very important. I have also heard that writing a book is like giving birth so perhaps it is more of a midwife role that mentors take on.

BW: You know, I think for me it is more mothering than midwifery as I often work with writers from very early on and then sporadically throughout until they publish. I’m just shy about assuming that identification for what I do. I think we all are often in need of some form of mothering!

ROOM: “Soul work” is such a wonderful term. Does your spirituality enter into your working with others? I can feel it in your writing, not fully articulated but it is always lying below the surface, the foundation of all that you do. Is this intentional?

BW: My spiritual practice of Buddhism is essential to my life, my writing, and my work with other writers. It’s always there. Always. But I don’t point to it very often as it feels more respectful and true if it infuses and informs.

ROOM: In your writing I always feel a sense of reverence for all life including your own process as a writer, a woman, and a mother. I have always admired that you do not billboard this, you essentially “show not tell” the teachings around Buddhism. Admittedly, this sparks curiosity, hence the question.

In your latest book, Oscar of Between, you mention how women regularly write about victims, and men about the perpetrators. Do you have a sense of what might be behind this? Was your writing of all the killings, the violence an attempt to counteract this pattern?

BW: Yes. I am deeply concerned about the ever-increasing violence in civilian life, and how a military strategy (invention of camouflage making WWI the first “war of deception”) has migrated into every aspect of civilian life. Men often wear camo when they execute random and mass shootings. Daily, my gender fluidity exposes me to very different sets of assumptions and interactions in public that have heightened my concern. Camouflage creates the ideal conditions for violence. I needed to understand what’s fueling it. As I got deeper into writing the book, it became evident that our rigorous training in gender roles around the world provides a global foundation—a shared language—for other “isms” such as racism. If men mostly continue to write about the perpetrators and women mostly continue to write about the victims then we’re stuck in an endless, escalating cycle.

ROOM: I found the ongoing nature of the disclosures compelling. If it had simply been one or two violent events they would have been easier to dismiss them as one-offs. I too have felt the need to explore the prevalence of violence and in my case violence against women has been of particular interest. This past weekend I spent two days with my Métis sisters in Ottawa as part of a pre-inquiry into the murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls. While there I had the privilege of hearing many stories.

Hearing the stories first-hand, feeling the pain of those who lost loved ones in violent ways was devastating. It made me realize the limits of the media sound bites and how formulaic, devoid of feeling they are. The way that you choose to share the details of current violent acts, sparsely and in clusters, had a similar effect as the close-in experience of a conversation with one who has suffered. Were you aware of this?

BW: Gradually. I kept thinking, okay, this violent event arose while I was writing that section but I hope I don’t have to write much about violence again, but then the event just kept arising and I finally had to accept they were (and are) a central part of our daily life. And that I had to allow them to enter the manuscript whenever they arose; it was sort of like being broadsided again and again but that is in fact, the truth of it. You are right about the safety of distancing and the numbing effect of the sound bites.

ROOM: You have also shared many beautiful experiences. Each of your books is a weaving of all that life offers; the sweet and the difficult. There is an immediacy in your work. We get to know you as writer, mother, a sacred witness to all that life offers us. You do this with each book that I have read. Sometimes you revisit an event and when this happens I am amazed at how I re-experience those moments with you and feel a deepening connection to what you are sharing. One story that really touched me was the one in which your mother intended to take a razor and remove some pages from your first book before she shared it with others. Such a powerful image. Cutting something so important and so beautiful seems such a violent act. It could be seen as an act of aggression against your truth telling.

BW: In Oscar of Between I mention that she intended to cut the first twenty pages out of my book (she never knew I knew her plan to do this) but my brother recently clarified that she indeed did razor blade the first twenty pages in one copy. When he saw it he reasoned with her “Your sisters will notice the first twenty pages are missing and they’ll imagine much worse things!” So, she just hid her copies of the book for a long time then eventually gave it to her sisters on the strict warning that they never show it or mention it to anyone. The section she cut out was about the breakup of my marriage. This threatened her camo. Her sense of safety. One of my cousins found a copy of it beneath the shelf paper in her mother’s underwear drawer decades later, after her ninety-two-year-old mother had died. One of the comments I have been hearing so far about Oscar of Between is that “It’s so intimate.” Which again, makes me feel shy. But then I realized it had to be, because Oscar had to be as transparent as possible in order to uncover the ever increasing array of camouflage manifestations that are profoundly harming everyone.

ROOM: I can relate to this urge to tell, to get close, and to offer intimate details of my life. I was just telling a friend that when I do this it is not just for myself, to unburden, but rather I feel that offering my story, being willing to discuss the reality of my life as a woman (which many women could relate to in varying degrees) is not for attention. God knows I don’t want that kind of attention. My mother’s sister is angry with me, my brother not too happy, but the story pushed on me. It left me no choice.

BW: It’s true!! I will attest, having watched you and worked with you over the years! Recently I have been saying that being a writer is a perverse profession! It’s sort of like parenting. If anyone sat you down and told you all that it demanded of you, most people would stand up and say “Thanks, but I think I’ll pass!” It’s hard, hard work in every respect. But, fascinating! The learning never stops.

ROOM: Yes and for many of us not all that lucrative. I hold my hands up to you and all others who have been willing to share your stories, your writing with us. We inspire one another and keep each other going. Is there one writer in particular that inspired you early in your writing life?

BW: Very early on while I was living in the United States and had been very active in students’ rights, anti-war, anti-racism, and feminism issues I was influenced and inspired by Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, June Jordan, Mary Daly, Joy Harjo, etc. It was a period in which poetry was often one of the strongest voices for social change. It was amazing.

ROOM: You have seen a lot in your thirty-five years as a writer. Do you feel we are making progress with the issues you mention above?

BW: Close in, I often think we are. On the larger scale it’s mixed; harder to tell. I am encouraged that once I came to trust being a person of between I have increasingly recognized an amazing range of other persons of between and experienced an increasing sense of curiosity and trust within myself and these other “betweeners.” It’s exciting as it cuts across class, race, gender, everything. So, it has the potential to create connections that we have been missing; missing to everyone’s detriment. I’m not suggesting that our very real differences should be pushed aside. But it seems that the connectivity of betweenness could create far more ground upon which to understand our differences more. What about you, what do you think?

ROOM: I am excited by what I see happening on social media. Many are becoming allies to one another. Declarations of support for those who are different go a long way. Sadly, we have the trolls. So close in . . . Yes. We are an ever widening circle that has agency and influence.

BW: There’s a thrilling inventiveness alongside of a bankrupt morality. Empathy has become a somewhat bewildering, even a passé thing. Yet. Happily, there’s almost always a “yet . . .” We long for something that touches us deeply. I was having a conversation the other day about the reader. I have a deep regard for the reader and began to tear up trying to explain why. It seems to go back to a childhood in which the adults weren’t able to listen because I saw things so differently than they did. This has continued through a lot of my adult life but I have found how to be with it in a better way. When I write, I listen a lot; listen, wait, listen until what needs to be on the page comes clear to me. I am grateful for my readers because they give me this most precious of gifts: listening. I hope I can give this in return.

ROOM: We have come full circle. “To note each other accurately; be noted accurately: what we long for.” There is so much wisdom in your words. They offer us a poignant reminder of how alone many feel. I was surprised by the response to my first book, page as bone ~ ink as blood. That it was received by so many in such a gracious and respectful manner was very healing. The connections with readers who commented were unexpected. I could see that some felt a deep kinship with my story and that others were grateful just to know another’s life. I was reminded of how, as a child, the stories of others, the weaving of hard truths and hope, made me feel less alone. Then this year I experienced joy for the first time in my life (that I can recall). It took me a while to realize that it was connected to the book and its acceptance. To be “seen” and to feel accepted is indeed powerful. And I have you, Betsy, your encouragement and your teachings around writing to thank for this.

BW: Thank you, Jónína!