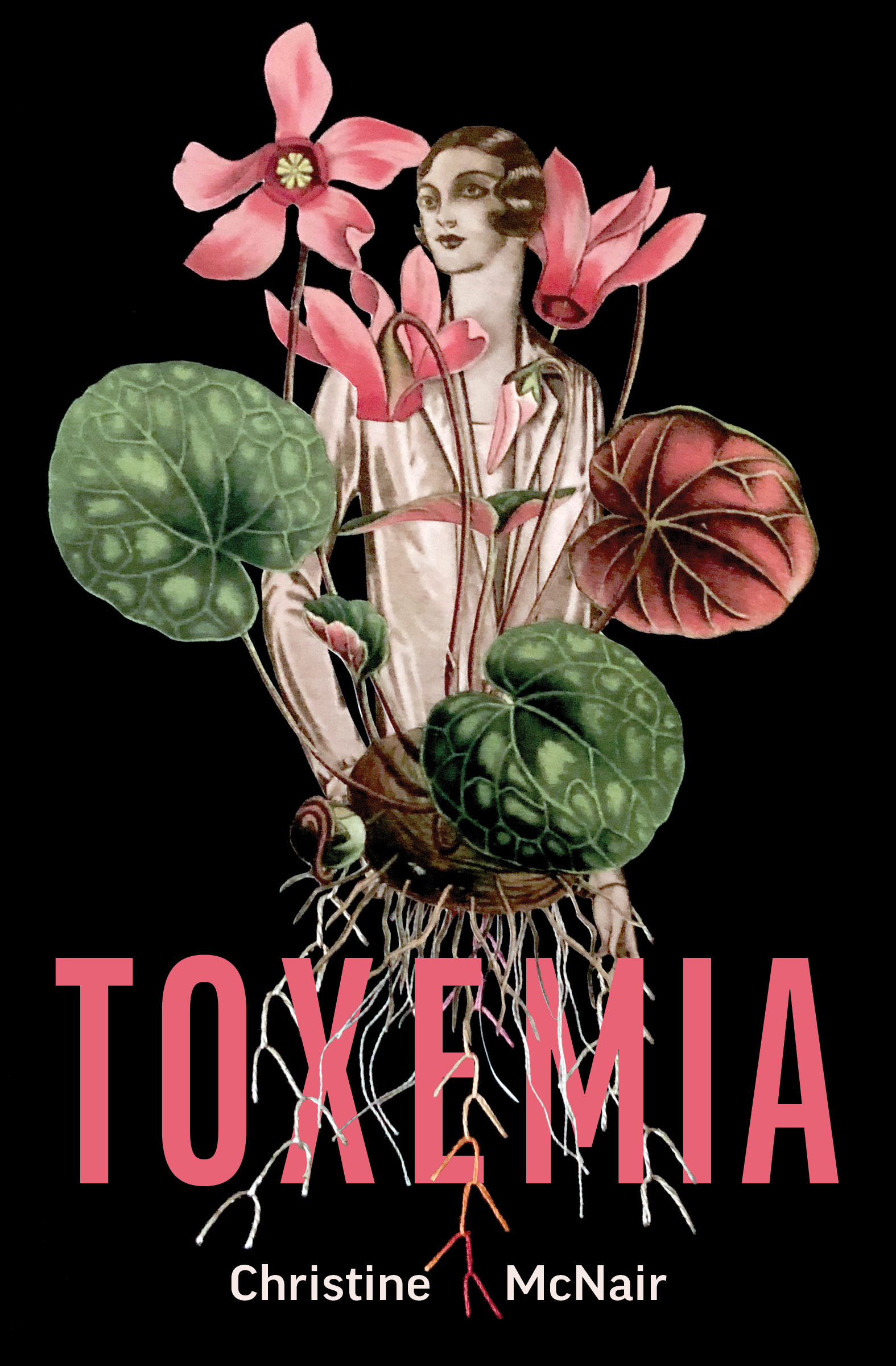

Toxemia

by Christine McNair

Book*hug Press

176 pages

$23

Christine McNair’s memoir, Toxemia, is a deeply personal account of her experiences with pre-eclampsia, a life-threatening pregnancy condition marked by high blood pressure, piercing headaches, double vision, and an impending sense of doom. The causes of pre-eclampsia are still not well-known, but experts believe it’s caused by abnormalities in the placenta during pregnancy. “The cure for pre-eclampsia is almost always delivery,” McNair declares in one of the book’s last chapters. The clarity of the statement contrasts with the pages that precede it: a memoir in flashes of poetry, photos, and essays. McNair, a book doctor based in Ottawa, is also the author of Charm, winner of the 2018 Archibald Lampman Award, and Conflict.

Toxemia opens with the image of a fourteenth-century illuminated manuscript depicting St. Margaret, who miraculously survived being swallowed by a dragon. The image on the parchment is smeared, the result of women kissing it in prayer to ask for St. Margaret’s protection during labour. The transcribed text, in Latin and English, is the first sign we are embarking on a scientific and spiritual journey to understand the word “toxemia.”

A term describing the presence of toxins in the blood, toxemia is also an old name for pre-eclampsia. Moving between memories of her pregnancies, emergency hospital visits, and her struggles with insomnia and depression as a bookbinding apprentice, McNair weaves a narrative history as lived through her body. At its heart, her investigation is about the ways the body rebels against the violence of pregnancy, as well as the intractability of illnesses that disproportionately affect women due to underfunding and under-research.

McNair tries to make sense of the condition in different ways: lyrically through vivid descriptions of symptoms and diagnoses, and genealogically by tracing the medical history of the women in her family—a great-grandmother who died at thirty-six, and her mother, who suffered a miscarriage before McNair was born. The most striking way, however, is analytical: one table lists the overlapping symptoms of a heart attack, depression, and the third trimester of pregnancy. Another compares the symptoms of pre-eclampsia and anxiety. Through these stark juxtapositions, McNair highlights the dangers and sacrifices implicit in the bringing of life into the world.

“The gestation from diagnosis to death was about nine months,” McNair writes when describing the progress of her grandmother’s glioblastoma, a destabilizing turn of phrase that borrows the language of pregnancy to describe her grandmother’s fatal illness. In Toxemia, McNair uses the shards of her life-threatening experiences to fashion a mirror for herself and for all women who have ever prayed for deliverance during their labour.