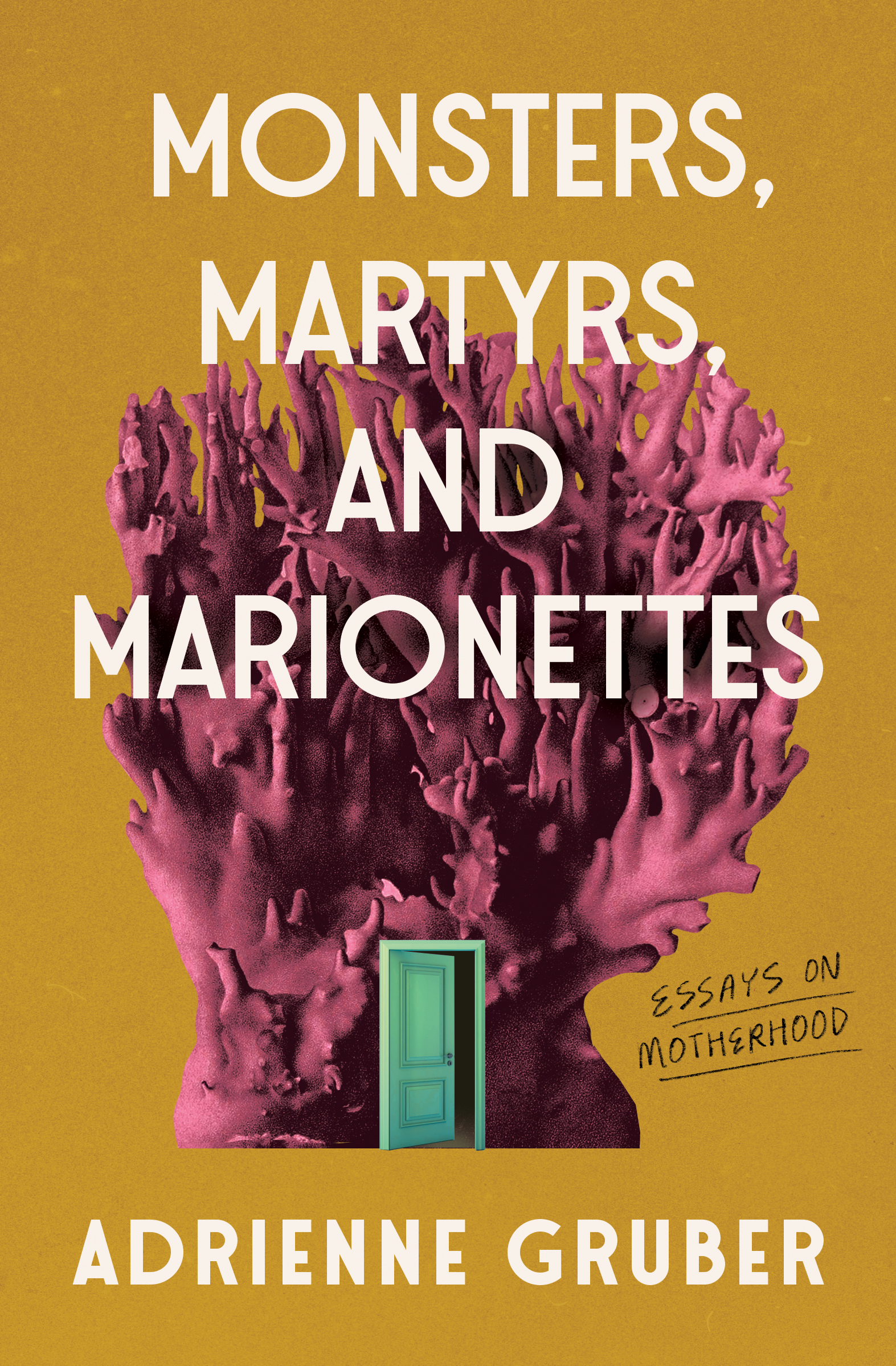

Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes: Essays on Motherhood

by Adrienne Gruber

Book*hug Press

146 pages

$23

Adrienne Gruber’s memoir-in-essays cracks open the institution of motherhood with a deeply personal exploration of her own experience. Each of the collection’s three parts reflects interwoven themes: the perceived monstrosity of negative feelings about motherhood, the societal expectation of selflessness in meeting the overwhelming needs of small children, and the resulting loss of agency over their own lives that many mothers feel.

Gruber uses the term “monstrous” to indicate feelings that violate the stereotype of unequivocally joyful mothering. She both loves her infant daughter and longs for her own space: “[w]hen she was a baby, I loved and loathed her constant physicality in equal measure.” Meeting the enormous needs of children can make us feel separate from ourselves, which Gruber alludes to as “the grief of my lost self.” Societal expectations weigh heavily:

I felt the obligation to perform motherhood, not so much for my children, or even my friends and family, but for the social contract I unknowingly entered into when I became a parent. Social media didn’t help, with its condescending memes written in self-righteous cursive—the days are long, but the years are short, being a mother is the most important job in the world—cheap shots unleashed at parents who just wanted to zone out for five minutes.

This observation resonates with me as a mother myself. I remember holding my own newborn in a public place, exhausted and overwhelmed, and a woman with a determined smile asking me if I was “enjoying it.” The comment instilled in me a sense of failure.

In addition to her insights, Gruber’s use of language on the sentence level and the overall structure of the book contribute to the impact of the collection. With three published books of poetry, she approaches her current subject with a poet’s sensibility. Each chapter’s title indicates its central theme. “Vigil for the Vigilant” opens with a description of Gruber’s husband’s night-time vigilance over their children, and by the end of the chapter we understand that Gruber is explaining this behaviour partly in terms of epigenetics—the study of how early childhood experiences can affect gene expression. She briefly mentions her husband’s Indigenous ancestry, then explores the concept of epigenetics, which gives readers some distance, then moves in again to focus on her husband. The narrative develops in a circular fashion, gradually going deeper into the difficult truth of the intergenerational trauma inflicted by residential schools. Alternating the intense and personal with the more detached and contextual is well suited to a difficult subject, as it gives readers space to decompress and reflect.

Gruber’s collection contributes to a nuanced discourse about motherhood. I appreciate her insights about the complexity of her mothering experience, expressed in well-crafted, poetic prose, and I expect that many other readers will as well.