“Your Skinny Daddy” is the honourable mention for Room’s 2021 Fiction Contest.

When your daddy is undocumented, you learn how to lie with ease. You learn how to protect him, to shelter his body. You learn, at the age of twelve, that secrets are an intimate, heavy thing to bear. You learn all of that in the back of a blue pickup truck winding through the Oaxacan mountains, nestled with your sister amongst piles of watermelons in the truck bed. You open watermelons and devour them one slice at a time, spitting the shiny seeds over the side.

Girls, I have a secret to tell you, he says. You love his secrets. You love his stories. The way he talks slowly when it’s important. You smile and grab your sister’s hand. Your eyes are wide. Your one dimple is deep in your left cheek. The wind is whipping all your hair around wildly. He sits up straight, clears his throat, and then gazes off into the distance before speaking. Your daddy’s black moustache is so thick and so wiry that it doesn’t move in the wind. Your daddy is so handsome and stern.

I don’t have documents, he finally says. You don’t know what to say. Your daddy understands that, and continues. I don’t have a birth certificate, even. The weight of his words communicates something. Something. But you don’t really get it. You will one day, though. Or rather, every day throughout your life you’ll understand new implications of this abstraction.

You can never tell this to anyone, girls. I was actually not born in Tamaulipas like I always say. I was born in Colombia. I arrived in Mexico with my best friend, Raúl.

Darío’s daddy! you both chime in.

Yes, your daddy says. We fled the war. We arrived and worked to buy papers.

Your daddy continues. You are my daughters, and you need to know the full truth of me.

You revel in this knowledge and proudly protect your daddy. You learn to pick up the lies, to be sensitive to the types of questions that get near this secret, and to divert conversations fluidly. You are a child and learning is what you do best.

But when your daddy is undocumented, by hiding him you also have to hide yourself. Just as he pretended until he became a “typical Mexican father,” using idioms and an accent from the North, you also feel like you’re hiding something. Mexico is the greatest nation on earth, as your daddy says. You say it too. You know so many other Latin American immigrant families, but you can’t relate because of the lie. You have learned to hold your tongue. But every time you meet a Colombian, you want to tell them, to find kinship. You don’t. It is odd, but you start to find a kinship instead with people from Tamaulipas. The lie comes to house sort of bastard belonging for you.

Your daddy’s best friend Raúl shoots himself in the head. His four brothers travel from Colombia to Mexico for the sole purpose of killing his wife, who they blame for making him crazy enough to shoot himself. Your daddy wants to be there for his friend, but the police are there, so he can’t. Raúl didn’t die—he blinded and gave himself brain damage. He was part of this only over the phone. Your daddy helped Raúl’s wife and Darío escape to Canada, and helped pay for the asylum that they put Raúl in. Your daddy doesn’t tell you this until years later though. Until he was a safe distance from the secret.

As time goes on, you realize how many secrets like this are involved. Big, sad stories and small details. It’s all shaped by the lie. The questions from your best friend. Your boyfriend. His family. “Wait, so your dad was born where?” Or your friend from Ciudad Victoria, who is so excited to meet your dad because people from Tamaulipas are “very rare in this region,” apparently very tall, and are “a different kind of tough.” You introduce them. You want to feel pride and kinship, but your daddy is evasive. You can spot this lie—he’s hiding. He pretends to be distracted, polite. He comments on how dangerous the area is. They talk briefly about the brutal murder of La Felina in Reynosa. Your daddy ends the conversation by pretending to get a call. Your friend is obviously disappointed from his conversation with your skinny daddy, who on top of it all, is not tall. As for you, you glean some good new talking points to use with other, future Tamaulipeños.

Tamaulipas. Tampico. You learn to be more specific. But it doesn’t matter because your aunts and uncles are all as Colombian as they come. Most of your cousins, too. They visit every few years. But there’s inevitably a point where it doesn’t make sense once you get close enough. So you don’t bring people to get that close to your daddy.

You start to test the edges of the lie. You experiment and tell some of your friends that your grandmother is from Colombia. Someone says you look so Colombian. Your heart swells. Your first girlfriend says that your ass is Colombian. You feel hot even though you know these kinds of comments are nonsense. But still, you feel some kind of sad, lonely nationalism. Then you feel like an idiot.

***

You cross the border with your daddy. Miami. The officer is Colombian. She turns to your daddy and levels with him. She says, You’re not Mexican, you’re Colombian. Your daddy is calm and handsome. He says no, and recites the lie about how his daddy was Mexican and didn’t talk much, and his mom was Colombian and talked a lot, and that’s why he has that accent sometimes. Especially with Colombians, like usted Señora. She doesn’t look convinced, but she waves you and your daddy through. The next day, your daddy spends the whole day in the motel room. You go for a long walk and you notice the “-ico” of the Colombian accent all around you in Miami. The “-ico” that hides itself both in the words “Mexico” and “Tampico.” You want to say “poquit-ico” when you ask for a bit of salsa with the arepas, but you don’t. You bring your daddy the food. He says “very nice,” but the next he day he buys Taco Bell instead. Both meals he eats in his motel bed.

On the news, you see a group of brave kids sitting in front of the white house with signs that say “undocumented and unafraid.” You wonder about that. You think, maybe your daddy is actually just paranoid, that he could just be more open about it and he’d be fine. Like those kids, and their families who are interviewed live on national television. But maybe it’s different in the US. You don’t know because you don’t talk about it. Your daddy hisses between his teeth and says “fíjate,” but never says anything about those kids. What it could mean. You feel shame. Then, you feel a worse type of shame for feeling shame.

You read The Undocumented Americans by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio and you hang onto those words like a hug in a closet—naughty and unsurveilled. Not because the stories are the same, or even similar, but because of the emotional subtext of smallness, of the futility of wondering, of confusion and confession and erasure. Most of all, because of the weirdness. You want to tell people the truth and talk it through, like you do with your other problems. You’re a talker. But that would betray your daddy. The lie about your Colombian grandma works well enough. You don’t, however, tell your daddy that you’ve been saying that. You wonder what he would say. Ojos que no ven, corazón que no siente, you tell yourself. Over time, you wonder about different friend’s and lover’s hypothetical reactions to this truth, too. If they would think it exotic. Or worse, if they would suspect, as you do sometimes, that it was all unnecessary. That it would’ve been fine for your daddy to have been honest all along. You spit.

Your daddy gets skinnier and skinnier. He moves to a new town. A town full of European and American tourists who have made their vacations a lifestyle. He moved to this town because nobody asks for papers there since it’s full of tourists. Ever. He builds a stone house that feels more like a fortress than a home. It’s cold. It echoes. You visit him there. Your daddy doesn’t really get close to anyone new. His other Colombian-turned-Mexican friend moves to this town too. His name is Mariano but he calls himself “Inti,”—the Sun God. Inti leaves his wife for a twenty-year-old. They don’t like this town. But Inti loves his twenty-year-old. Your daddy loves his house and he doesn’t need to leave it much. He feels safe.

Until one day, his neighbour dies. She was a young woman, her name was Leslie and you knew her too. She was found two days later rotting in her bed. It’s a mystery, so her family calls an investigation. The police come to ask all the neighbours benign questions, but your daddy locks the house. Locks himself in his room. Sits in the only corner where you can’t see in from the window. Your other neighbour tells the police that your daddy went on a trip. But for seven days, your daddy stays like that. When the police leave the neighbourhood, your daddy pries himself from his corner. He doesn’t tell this to you until the next time you visit from Vancouver, because he doesn’t trust phones. You imagine the popping sound of his joints when he finally stood up from crouching in that corner.

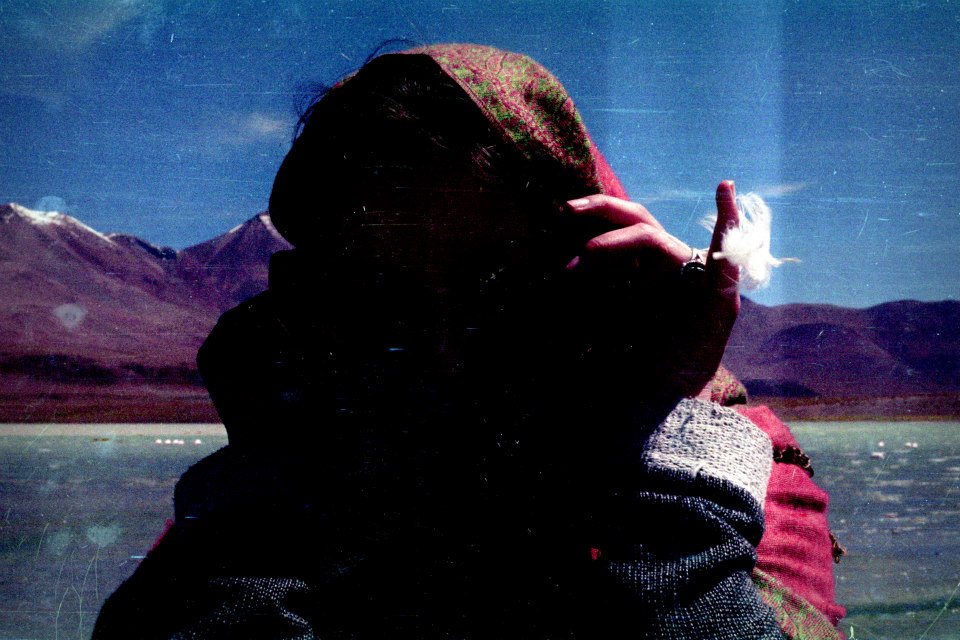

You feed your daddy as much as he will eat. He’s gotten so skinny. You remember the sweetness of the secret in the back of the blue pickup truck and it feels far away. The watermelon sugar bitter. You go for a walk outside together. Your skinny daddy is a bent version of himself, but his moustache stays still in the breeze as before. You protect him. You feed him.

He has grown small. But the older you get, the more you wonder whether this was really necessary. What if your daddy hadn’t hidden this whole time? Would the shape and bend of his body be different? But you are afraid of what the answer might mean. You don’t know how to fix this. You only know how to produce a range of lies, so you continue on.