Tansi, hello! Welcome to our online celebration of Black History Month with the Indigenous Brilliance Collective and Room Magazine. For the month of February, we will be sharing weekly content on the @indigenousbrilliance Instagram page, as well as over here on the Room website. This month we will explore different media recommendations from Patricia Massy of Massy Books, share interviews and content from featured Black and Black/Afro-Indigenous creatives, as well as dive into thought provoking questions, all related to the topic of Black/Afro-Indigeneity on Turtle Island.

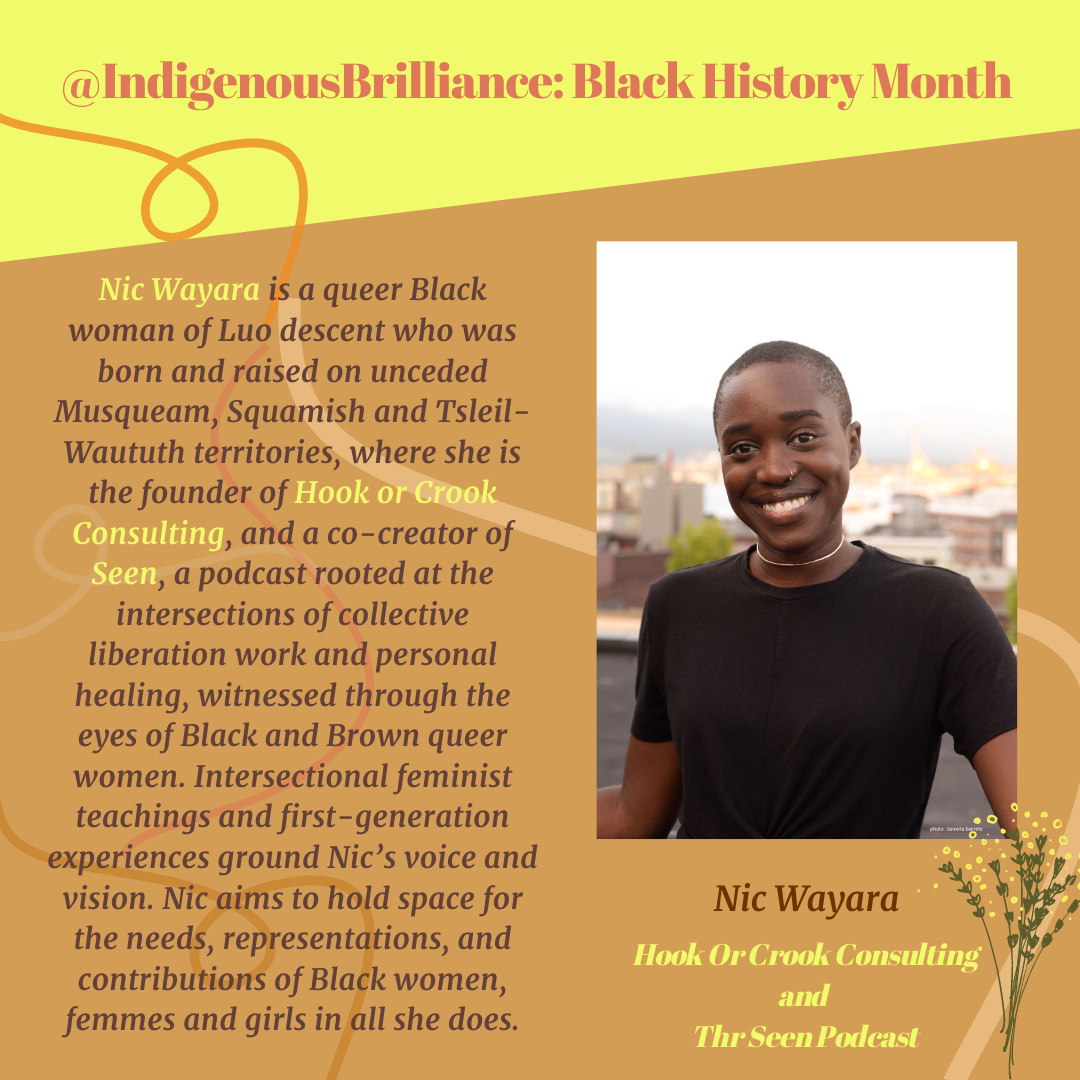

Today we will be exploring the ways in which Black and Indigenous people have been in solidarity throughout history. Featuring an interview with Nic Wayara of Hook or Crook Consulting Co., we will dive into some conversation and imagining of ways that we can continue to show up for each other, transcending structures of lateral violence and colonial systems of oppression within and between Black and Indigenous communities. We hope you enjoy it!

Black and Indigenous folks have shared a fight for sovereignty and liberation since the colonization of Turtle Island and the inception of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. In many ways, Black and Indigenous people share collective and cultural values in our political and community practices, going back to time immemorial. A collective resistance and fight for freedom from the settler colonial state is something that I believe can unite Black and Indigenous folks in our various political and cultural movements.

However, I have observed, discussed and experienced ongoing anti-Blackness within many Indigenous communities and spaces, resulting in a challenging co-existence and intersectional, cross-cultural liberatory practice. I have also noticed a struggle for some Black folks to acknowledge the territory we are on, and our shared histories of colonization with Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island. Rather than growing our communities together, it often feels that we are in competition for liberation, and through this confusion, we end up harming our kin and replicating tools of settler oppression between BIPOC communities. This is not our way, and as a Black-Indigenous person, I dream of a future in which we can deconstruct tools of settler-colonialism within our own marginalized communities, and strengthen bonds of solidarity between Black and Indigenous folks on Turtle Island.

In reference to an episode of the podcast Medicine for the Resistance titled Black and Indigenous with Azie Dungey, Auntie Edzi’u reminds us that even as Native folks, we must seek out education on the ways in which white settler colonial policies strategically pit Black and Indigenous folks against each other. Edzi’u suggests that this only serves to further assimilate and oppress both Black and Indigenous people. Edzi’u remarks that this has been the basis of anti-Blackness that we see within various Indigenous communities, as well as anti-Indigenous rhetoric.

They go on to encourage their community of Indigenous kin who are non-Black, to “confront their anti-Blackness, how white supremacy pits us against each other and how that ostracizes our Afro-Indigenous cuzn’s.”

Edzi’u calls in their kin to question their own proximity to whiteness and to hold ourselves and each other accountable to our Black and Afro-Indigenous relatives. We encourage you to check out the Medicine for the Resistance podcast which sparked this reflection for Edzi’u and ourselves at the Indigenous Brilliance Collective.

The topic of anti-Blackness within Indigenous communities, and Black/Indigenous solidarity is of course a challenging and complex topic. I, by no means, claim to be speaking any absolute truth. Rather, I hope that this exploration will ignite a curiosity in you to position your own self within this dialogue, and to do some critical reflection and personal learning of your own.

The topic of anti-Blackness within Indigenous communities, and Black/Indigenous solidarity is of course a challenging and complex topic. I, by no means, claim to be speaking any absolute truth. Rather, I hope that this exploration will ignite a curiosity in you to position your own self within this dialogue, and to do some critical reflection and personal learning of your own.

Building solidarity between our diverse communities and centring Black and Indigenous experiences equally will take a significant amount of deconstruction and humility from all of us in order to build an inclusive and liberatory collective future. This future should include all minority groups as well as our allies who hold us up and walk with us toward our sovereignty, liberation, and freedom.

To help me explore this topic further and to share a bit about the work she does, I have had the great pleasure of interviewing Nic Wayara of Hook or Crook Consulting Co.

Nic Wayara: My name is Nic Wayara, I am a Black Queer Woman, I am second generation “Canadian.” My ancestors are Kenyan, and my people are Luo. I was born and raised on unceded Musquem, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh lands in Vancouver, and I am the founder of Hook or Crook Consulting. It just launched at the beginning of 2021, which I am really thrilled about. It’s an equity, diversity, and inclusion company that draws on decolonizing practices and values, intersectional feminism, and anti-oppression practices to support teams and individuals in the places where we spent a lot of our time, which is often at work. My aim is to explore how we cultivate the conditions of care within organizations that historically haven’t always been the safest places for people who experience different forms of marginalization.

Whether you’re racialized, or if you’re of a marginalized gender, or have historically experienced a lot of barriers–when you enter into work, you’re still that person. And oftentimes, I’ve gotten the sense that there are a lot of opportunities to better support marginalized folks. I think the ways that organizations have been doing things aren’t really working.

To an extent, Hook and Crook was born out of trauma. It was one of those things where I was at an organization that was quite harmful to me and others, and in my own personal healing from that job experience, I realized that what I needed to do was help transform organizations and really shift the conditions that a lot of us are forced to work within. So that’s the impetus for Hook or Crook. My focus is how to support the more relational pieces that I think are really important when it comes to equity, diversity, and inclusion work. Starting Hook or Crook was influenced by the podcast Seen that I co-founded and co-host with my good friend Premala Matthen. Seen is another meaningful piece of work that I’m really grateful to be part of. It’s a podcast rooted at the intersection of personal healing and collective liberation work, through the eyes of Black and Brown Queer Women. So, we try to create this space for us to both learn in public and share with each other and talk about some of the things that we’ve personally witnessed or experienced, or some of the things that have challenged us as folks who are trying to do the work in a good way.

Karmelle Cen Benedito De Barros: I have been listening to your podcast for quite a while now and I’ve always found it to be a very comforting voice. Just hearing some experiences of people of colour and femmes specifically living in the same city as I do, and hearing you two speak so openly about your challenges and experiences of growth and being able to complain together and problem solve, and being so transparent with all of it, I think is so beautiful and really inspiring. And then the fact that you’re starting your own business makes me feel so happy. I’m excited to hear that you believe in yourself and you believe in the work that you’re doing and you’re really practicing what you preach by taking your voice and reminding yourself that what you have to say is important and your perspective is important and that you have something to offer people, and that people need to listen. I think that’s dope and I’m really excited to see all of the work that you do in the future.

NW: Thank you so much, and it really means a lot to me that you see the podcast that way. It’s always really affirming. I think for me, if somebody feels that the podcast resonates, then it’s worth it. If this is supporting somebody else and their ability to honour the fullness of their identity and their experience, and even the imperfections of the things that they don’t know, and just feel alright in the “not knowingness” of it all, I think that there is a lot of good potential and possibilities in that space.

KB: Yea, the word humility comes to mind for me. It’s like, the ability to sit with imperfection is necessary for growth and I think you model that really well in the podcast and the work that you do.

NW: Thank you.

KB: I know community care and development is something that centres or grounds the work that you’re doing and I’m wondering if you have a few words that come to mind when you think of community care, and what are some key ingredients to intersectional community building for yourself specifically and also focusing on Black and Indigenous people?

NW: One thing that Lala and I talk about in our podcast that has been helpful for me has been knowing that there’s a deep connection between the individual and collective. Balancing between both of those two has been really beneficial for me. So, what that’s meant is looking beyond myself and knowing that there likely are other people who I can do things with, who I can collaborate with, who I can learn from, and almost freeing myself of the pressure, of you know, “being perfect.” Just knowing that the most meaningful piece of, for me at least, collective liberation work is the kind of transformation that can take place when you’re able to be in relationship with other people. And so, for me it’s like being a natural extravert. I love being around people. COVID-19 has been really difficult and for me to be able to have the things that I need to feel good about living in the world. And that has been compounded by all the things that have been happening over the past year, like the racial justice uprisings.

NW: Something that I’ve noticed since the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor last year, is that we’ve increased our ability to understand each other at our different intersections. What I’ve seen online specifically is a lot more Black folks understanding or witnessing and really seeing our Indigenous kin and siblings and family, people around us, and communities. They’re like wow, there’s things that we’re experiencing that are similar. There are some shared things that are happening in our experience, inhabitance, and of the world within settler colonialism. And then seeing a lot of Asian folks standing in solidarity for Black Lives and just, our ability to come back to a—or, maybe not come back to—but, you know when you look at all the rich history of the Black Panthers, and you see the interconnectedness of the struggles that folks were embracing and supporting. I guess what I feel is that those histories are alive. And what I’ve witnessed is a lot more of us looking to each other and uplifting one another. We could talk for a long time about how we need more of that, but that’s been really affirming for me, and that’s something I try to think of as I’m doing what I do.

KB: Totally. Sometimes I wonder if it’s something to do with the specific city that we live in. I haven’t lived anywhere else, but Vancouver is a city that feels almost kind of segregated, or like there are small groups of people that occupy space or experience community in different areas, but that it all feels very spread out and kind of fragmented. And then for me it’s like, well of course we’re not all experiencing this intersectional solidarity that we’re craving because we’re not really operating in our daily existence together in these ways. And you live on the North Shore, I use to live in North Vancouver as well and that feels like a completely different world from Downtown Vancouver, and so we’re not even seeing people who we could be relating to in deeper ways, we’re not even seeing or interacting with each other on a daily basis and I wonder if that impacts the way that we’re standing in solidarity with each other or feeling part of a movement that’s bigger than ourselves or our own experience.

NW: Yes, I think the geography in Vancouver…everyone’s in little silos. One thing that I really appreciate before COVID was the amount of work that I’ve seen folks pour in to create spaces where specifically queer and trans people of colour can come together. I think specifically of DJ Softieshan and the work that she’s done by cultivating community events like LevelUp, which is a queer, Black led hip-hop dance party. I’m excited about the possibilities after us having this incubation period. After having been able to benefit from events like those that she and so many others were putting on where folks could talk and think and come together as queer and trans people of colour. I feel like in our racialized communities we’re now at the point where we’re like, actually colonialism is something that we can all talk about if we really wanted to.

KB: I think, like you were saying earlier, this pandemic has kind of offset a pretty large-scale reaction or realization or reawakening to the fact that Black and Indigenous people are experiencing extreme amounts of colonial violence on Turtle Island and it’s been interesting to see. Maybe it’s just that people have more time to open their eyes or really reflect and think about what’s going on in this world, and in a lot of ways it’s like “Damn, y’all are really surprised about this?” or it feels new to a lot of people. I think that this whole pandemic has been a really good time for reflection for a lot of folks, and like your saying, reflecting on a lot of the bad, but also on a lot of the positive things that we were experiencing before our whole realities changed, and then looking forward into the future.

What is something you look forward to in terms of community building and sharing space to continue this decolonial work outside of a global pandemic?

NW: I co-organize a series of monthly connections called Black Youth Summit, where a bunch of Black millennial/Gen Z aged leaders and organizers across the Lower Mainland and the Island come together virtually. It’s just been a lovely space for us to get to know one another and the work that we’re doing, what motivates us. We’re trying to map out our visions for Black futures and co-design how do we future Black lives, and how we centre the issues that are important to us, how we speak with one voice, and all these kinds of things. More than anything else, I just can’t wait to have us meet in person, because we started our connections using Zoom and I want to be able to be in the same space with other young Black folks. Just like, share the air, share time and space and real eye contact. That seems really appealing to me.

Something that you had just mentioned about the time we spent in COVID and how it’s been a reflective time for a lot of folks…I think of what COVID has done and how it’s exacerbated a lot of the shitty things that were already not working for folks who are marginalized, so everything became more pronounced. I think for those of us who have any privilege (myself included), it’s made me realize how non-negotiable a lot of this work is and how it must continue. And there really is no going back. So, I’m excited again for us to share physical space with each other but also to see all of the fruits of everyone’s labor, having been radicalized by these moments that we’ve been having in relative isolation, with all the grief we’ve been experiencing, and the loss and witnessing a lot of inaction and the ways that white supremacy plays out and manifests in really egregious ways. That to me, that’s the possibility piece, and I think people are sort of waking up.

KB: I definitely agree. And I’m also looking forward to seeing people in the future in real life. It’s really weird trying to make eye contact with you right now, because I’m not actually looking into [laughs]

Just one last question. So, I know before we started recording the conversation we were talking about rest and how you’re taking it easy this month, and I think that’s really important and inspiring to me that as a Black person you’re not putting any extra pressure on yourself to produce more than you feel comfortable just because it’s Black History Month.

In the spirit of Tricia Hersey and The Nap Ministry, I think it’s important that we’re really listening to our bodies and not conforming to any external expectations of productivity or performance of our Blackness for the people around us. Despite our desire for folks to do that learning work, it shouldn’t be on us to be the teachers all the time. I think you’re setting a beautiful example even just for me right now in hearing that you’re taking it easy this month. I guess my question for you would just be, if you have any words of advice or affirmation for Black and Indigenous people who are committed to this decolonial work as a lifestyle not just as a one month celebration, how do we sustain this work and take care of ourselves so that we can take care of each other?

NW: Wow, that’s a really good question. I almost want to know somebody else’s answer to that. I guess, trusting that we are interconnected, interrelated, and interdependent on each other. Letting that be something that can sustain us, because something I have felt is: if I don’t do this, if I don’t say this out loud, if I don’t post this thing on Instagram, if I don’t have this kind of conversation, then nothing’s going to get done. I think about the urgency of white supremacy, especially having this “George Floyd effect” where a lot of white folks are going “I need to not be racist anymore, immediately.” And what’s happening is lots of labour is falling at the feet of racialized folks who are harmed under white supremacy.

So I think just knowing that if I don’t do it, that somebody else is going to be okay to do it, and that once I’ve gotten my rest in, that I can come back to community or come back into the work. Knowing that the rugged individualism, urgency, and the pressure to fix all the problems we didn’t even create…it’s not natural. And it’s okay to need things like resting, like tuning into our bodies, catching up with our relatives or people that love us and affirm us, saying no, having those lazy days, all those pieces are important. Going back to one of the things I was saying before, about being interrelated and interconnected, I also think it’s important that we’re dreaming about the future and all the possibilities that could exist. I’m personally committing myself to being in closer relationship with Indigenous people of Turtle Island. I feel that is my own decolonizing work. All of those things connect: coming into closer relationship with each other and understanding each other and understanding our own histories and origins and where they intersect.

I’m reading more about my own people’s resistance to colonization, it makes me go, “holy shit,” the ways that my people were seen under colonialism in Kenya are so similar to the ways that Indigenous people are seen on their own lands, on Turtle Island. So, once I have those links, I can’t un-know that, so then I’m like, now what am I going to do about it? How am I going to show up for Indigenous people around me? How am I going to uplift them? How am I going to expect more of myself? Hopefully we’re all expecting more of ourselves, and we’re invested in how connected we are, at least when it comes to the histories of what have catapulted us to this moment now. We have survivors in our DNA so how do we want to show up for each other. That’s something that I’ve been thinking of. That’s a really long-winded answer.

KB: Beautiful though, and you touched on so many important things. I think a major thing that’s coming up for me is the reminder of the fact that we aren’t living in our natural state, we’re not living in our natural way of relating to each other and the whole point of this decolonial process is that we’re coming back to something and we’re building something new. There is space for all of us to exist in these ways that feel safer and more comfortable and more natural for all of us together, and I think that something that you’re touching on as well is that natural state of being in relation to each other for Black and Indigenous people is a quite similar way of being, knowing that your community is there for you, knowing that we all have a place, knowing that when we need rest we can take that space and we’ll be taken care of, and that when we come back, we always have something to offer.

Building off of what you’re saying, for the future for community that is in solidarity and is intersectional and inclusive, we all must remember that we have a place, and that we all know that we can be taken care of, and that doesn’t to have anything to do with race, or culture etc. We’re building a decolonial future, that means that there should be space for all of us, and for those of us that have experienced the most oppression, is that we’re prioritized of course, but that there’s space for everybody. I’m excited for that.

NW: Me too. I really am. There’s space for everyone. That is the gold star for me. So thank you.

As Nic mentioned in our interview, “there are a lot of opportunities to better support marginalized folks” and there are a lot of opportunities for Black and Indigenous folks to better support and show up for each other.

This month specifically, I echo the words of Auntie Edzi’u as I invite you to ask yourself:

- What am I doing to show up for Black, Afro/Black-Indigenous folks?

- In what ways do Black, Afro/Black-Indigenous people experience anti-Blackness within my own communities?

- How can I unlearn colonial notions of anti-Blackness that impact the way I navigate this world?

If you are a non-Black person of colour, I invite you to be kind with yourself as you challenge your own perspective and biases in relation to anti-Blackness. If you are of white settler ancestry, I challenge you to acknowledge your power and privilege with great humility, and to support Black folks who are dedicated to doing this work of education, liberation, activism, and community building. Uplift these people, support them, follow their work, cite them and share their knowledge, and never take us for granted.

As Dante Stewart says, “Black History Month is not simply asking, “how can I remember and learn about Black people?” It is all of us asking, “how can we love Black people by seeing them, hearing them, relishing in them, and creating a world where Black people feel loved, inspired and protected?”

And to the Afro/Black-Natives out there, keep existing and embodying yourself fully. You are sacred.

And to the Afro/Black-Natives out there, keep existing and embodying yourself fully. You are sacred.

Until next week,

Karmella and the Indigenous Brilliance Collective at Room Magazine