Kayi Wong discusses feminism, young adult literature, and collaboration with beloved graphic novelists Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki. Originally published in Room issue 38.2 “How We Relate.”

Originally published in Room issue 38.2 “How We Relate” (June 2015)

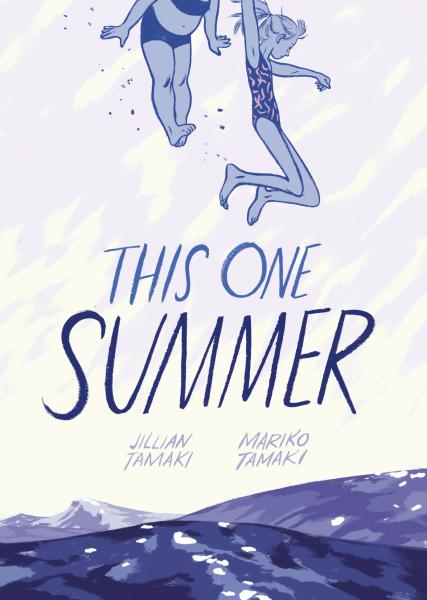

In The New York Times, reviewer Susan Burton calls cousins and collaborators Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki’s latest graphic novel, This One Summer, a “moving, evocative book.” “If I worked at a bookstore,” she says, “I’d be hand-selling it to customers …” It’s a sentiment that’s easy to relate to—like their 2008 graphic novel Skim, This One Summer (2014) combines smart, realistic dialogue with gorgeous illustrations to incredible effect; it’s the sort of book you want to shove into the hands of everyone who is or ever was on the verge of becoming a teenager.

In 2015, This One Summer became the first graphic novel to receive a prestigious Caldecott Honor and the second to receive a Printz Honor. It was also nominated for an Eisner Award, an Ignatz Award, and the Governor General’s Awards for both children’s text and illustration—with Jillian Tamaki winning in the latter category. In the following interview with Room editorial board member Kayi Wong, Jillian and Mariko discuss feminism, young adult literature, and their creative processes, as well as their past and upcoming projects—both individual and in collaboration.

ROOM: Can you tell me about the process of collaborating on This One Summer?

JILLIAN: Mariko kind of comes up with an idea and then we work out a pitch together and that’s what we use to sell the book. Generally, the story part of the process is all her. She writes out the dialogue like how a play would be, and I do a sketch of the whole book. Then it’s a lot of editing back and forth before we even show our actual editor. After it gets sent to an editor, I have to spend a year just to make the book.

MARIKO: It is a very collaborative process. I think one of the common misconceptions is that because there’s art and words, they’re two different things. But really, it’s a very interconnected way of working, which is not to say that I draw, but the actual making of the story is very intricate. The real goal I think for the both of us is to have something that feels like a single story being told, not a story being told twice, once by words, and once by images.

ROOM: How would you say the process is different from other collaborations you’ve done?

JILLIAN: The books with Mariko are definitely the most intense and personal collaborations that I do. Mariko is an incredible collaborator who lets you take ownership over the thing even though it is her “story idea” or something like that. I am an illustrator for most of my time. Even images that appear in magazines are collaborations in a way with the art department and designer, so I actually really like collaborating. But the things I do with Mariko, I have a lot more ownership over and there’s a lot more of myself in them. I definitely view them as a very special thing. I don’t feel like an illustrator, when I do comics. The word “creator” is such a fussy word, it’s so high in the sky, ephemeral, but it’s just the most accurate word to use in terms of what Mariko and I do.

JILLIAN: The books with Mariko are definitely the most intense and personal collaborations that I do. Mariko is an incredible collaborator who lets you take ownership over the thing even though it is her “story idea” or something like that. I am an illustrator for most of my time. Even images that appear in magazines are collaborations in a way with the art department and designer, so I actually really like collaborating. But the things I do with Mariko, I have a lot more ownership over and there’s a lot more of myself in them. I definitely view them as a very special thing. I don’t feel like an illustrator, when I do comics. The word “creator” is such a fussy word, it’s so high in the sky, ephemeral, but it’s just the most accurate word to use in terms of what Mariko and I do.

MARIKO: Every collaboration is different. It’s intimidating to work with someone as talented as Jillian—not to say that the people I work with otherwise are not talented. I think we share an idea of women’s perspectives, a kind of feminism that wants to look at a specific sort of life experience, which I don’t necessarily share with other collaborators. The great part about working with Jillian is that we’re able to work really well together, but also be very clear about what each other does in the relationship. I’m not editing her art and she’s not editing my words, but we are in the space with the book where it comes together. I think it’s also nice to know that I completely trust her artistic sensibility one hundred percent. Having complete faith in someone else’s part of the deal lets you focus on what you want to do.

ROOM: Have you always known that your storytelling styles would fit inimitably together?

JILLIAN: I feel like Mariko’s work is very emotionally resonant in a way that I learned a lot from. She’s very good at hitting those emotional notes that are nuanced and don’t have a name you can identify them with. Maybe she’s more in touch with her emotions or something [laughs]. Emotional resonance ultimately has more power than art style or cool factor. Part of what is great about working with Mariko is that so much of what she writes is unsaid. A lot of her work is about non-communication, and blockages between people. It’s not in the words, it’s what you’re not saying. And so what I get to do is communicate that through body language, and the unspoken things are where I get to play. I love filling in the gaps a little bit in sort of an enigmatic way.

MARIKO: I knew that she was an incredibly talented artist, but I didn’t know that we were going to be able to tell stories together the way that we were. Before collaborating on Skim, a side of me was just picturing Skim writing on the pages of a physical diary, and never really looked outside of that experience. When I first saw Jillian’s take on Skim, I was just amazed to see the combination of Skim having this internal voice, and this girl being put in the world. Jillian took Skim outside of this diary and it is the reality that I was focusing on in the diary versus what that physically looks like when that person is walking around in the world. I’m a very introverted person, so I think that it kind of opened me up to a perspective that I would not have come to on my own. It really made me want to do comics more after I worked with Jillian, but also I think with This One Summer, it made me want to be even more layered in terms of different worlds, different realities, and different perspectives. One of the things that is really popular right now is multiple perspectives in literature where you have a lot of stories that are shifting back and forth, and I think part of that is this desire to get into more than one person’s point of view.

MARIKO: I knew that she was an incredibly talented artist, but I didn’t know that we were going to be able to tell stories together the way that we were. Before collaborating on Skim, a side of me was just picturing Skim writing on the pages of a physical diary, and never really looked outside of that experience. When I first saw Jillian’s take on Skim, I was just amazed to see the combination of Skim having this internal voice, and this girl being put in the world. Jillian took Skim outside of this diary and it is the reality that I was focusing on in the diary versus what that physically looks like when that person is walking around in the world. I’m a very introverted person, so I think that it kind of opened me up to a perspective that I would not have come to on my own. It really made me want to do comics more after I worked with Jillian, but also I think with This One Summer, it made me want to be even more layered in terms of different worlds, different realities, and different perspectives. One of the things that is really popular right now is multiple perspectives in literature where you have a lot of stories that are shifting back and forth, and I think part of that is this desire to get into more than one person’s point of view.

Comics allow you to really subtly do those different perspectives without necessarily telling you explicitly what anyone is thinking, just what they’re saying or what they’re doing, which is incredibly valuable I think in storytelling.

— Mariko Tamaki

ROOM: Can you tell me more about your treatment and representation of a diverse cast of characters in your works?

MARIKO: Well, I’m a feminist, and I have a concept of equity, equality and all of those things, and I understand where representation fits into all of that. Skim is about a young Asian person, and (You) Set Me on Fire is about a young Asian person, in part because I think that there is not necessarily a lot of young Asian people in books. When I was a kid, there was Obasan, that’s like the only book you can read about a young Asian girl. I think it is really important that the people you see and whose stories you see unfolding are not just the same character every time. Skim is Asian but she’s not I’m Asian and therefore I have a mother who wants me to practice the piano all the time. Like, there are diverse experiences of race.

JILLIAN: I’ve never been pushed to emphasize the aspects [of race and gender] either, and yet, I feel like Windy [This One Summer] is a lesbian kid and she’s going to grow up to be a lesbian. It is part of her character, but it’s not something that we have to address and make a thing about. In that way I really appreciate just straight representation and not “DIVERSITY!” To just make an example of it, a positive example. It is not my interest to do any of that pedantic stuff.

ROOM: Was there any resistance from your publishers when it came to queer characters or characters of colour?

JILLIAN: We have been extremely lucky in that we have never heard from any of our publishers that it would be great if “she could be more ethnically ambiguous,” or if “she could be more attractive or skinny.” Never once. To be honest, I feel like it’s only been something that people have been excited about. I’m not trying to sound like a Pollyanna or something, it’s just that the publishers we have been involved with have it as part of their mandate to produce more diverse books.

I think that’s like a little bit of a secret: to have happiness with your work is to get involved with people who share the same values. — Jillian Tamaki

ROOM: Can you tell us more more about the choice of purple in This One Summer?

JILLIAN: On one level I just thought it would look cool. A lot of vintage manga is printed in that colour and it looks awesome. It is also appropriate because it tinges the whole thing in a slightly unexpected way and that colour [dark purple, purple-blue] to me doesn’t have such strong associations like say sepia or pink. It was a colour that seems neutral but gives an emotional feeling in a different sensory reaction.

ROOM: In a previous interview, you said that you allow yourself to not stick to a single illustration and artistic style. That seems like an unconventional approach to illustration and graphic novels.

JILLIAN: I’m sort of at a point right now in my illustration career where it’s like I’ve accomplished a lot of things I want to do but I still have thirty more years of career left and it’s like, okay what now? Do you continue on with that thing you found success with? That doesn’t seem smart because it’s a very trendy industry, and what’s working for you now is almost guaranteed not to work for you in five or ten years. I think your happiness is worth something. If you want to be laser focused on one thing, do it, that’s great. I’m almost jealous of you. It’s just my personality that I get bored and anxious if I don’t feel like I’m moving forward or improving. At some point, I gave myself permission to like change, and hopefully, evolve for the better.

ROOM: Mariko, you have an expansive academic and artistic background. How did you come into writing essays, and eventually young adult books and graphic novels?

MARIKO: I started creative writing in high school and it was the best thing I had ever done. When I came out of the closet in university, one of the first things I found was this scene of lesbian spoken word artists. I did a lot of spoken word and I loved it. I started doing open mics too, but I was terrible at it. I was trying to do what someone else was doing, I was trying to do really sincere spoken word art, and that’s just not my forte. When I came back to Toronto, I lived with Zoe Whittall, who is an amazing writer and poet, and I think that just kept me in the game of wanting to be a writer. I got a Diaryland [blog] and took a creative writing class; from there writing became less about just reading something at a microphone. It became more about taking something and editing it, having it be something beyond what just came out of my head that one time. It was about revisiting it, and crafting it, and fixing it, and really finding humour, which I was really drawn to. Those pieces started getting published as collections of essays [True Lies: The Book of Bad Advice]. At the same time, it seemed like I was never going to get a job other than being a secretary with my Bachelor of Arts, so I decided to get my doctorate and become an academic because I loved it. I had kind of given up on the idea of writing for anything more than just pleasure. I was writing little essays for Kiss Machine then, and during one of their tours I met a woman who was putting together a short comic book series, and that’s how Skim started off. It was eventually picked up by a young adult publisher and suddenly I was a young adult novelist. It was one of the first times I became what I am because someone else told me what I was doing was this. I just thought I was writing about teenagers, I didn’t know that that made anyone a specific thing. It’s been really great to just have someone else say, “Well, you like doing this and you do this relatively well, so you should just keep doing it.” And I’m like, “Great! Because I like doing it.” So that works out really well. Let’s do that.

MARIKO: I started creative writing in high school and it was the best thing I had ever done. When I came out of the closet in university, one of the first things I found was this scene of lesbian spoken word artists. I did a lot of spoken word and I loved it. I started doing open mics too, but I was terrible at it. I was trying to do what someone else was doing, I was trying to do really sincere spoken word art, and that’s just not my forte. When I came back to Toronto, I lived with Zoe Whittall, who is an amazing writer and poet, and I think that just kept me in the game of wanting to be a writer. I got a Diaryland [blog] and took a creative writing class; from there writing became less about just reading something at a microphone. It became more about taking something and editing it, having it be something beyond what just came out of my head that one time. It was about revisiting it, and crafting it, and fixing it, and really finding humour, which I was really drawn to. Those pieces started getting published as collections of essays [True Lies: The Book of Bad Advice]. At the same time, it seemed like I was never going to get a job other than being a secretary with my Bachelor of Arts, so I decided to get my doctorate and become an academic because I loved it. I had kind of given up on the idea of writing for anything more than just pleasure. I was writing little essays for Kiss Machine then, and during one of their tours I met a woman who was putting together a short comic book series, and that’s how Skim started off. It was eventually picked up by a young adult publisher and suddenly I was a young adult novelist. It was one of the first times I became what I am because someone else told me what I was doing was this. I just thought I was writing about teenagers, I didn’t know that that made anyone a specific thing. It’s been really great to just have someone else say, “Well, you like doing this and you do this relatively well, so you should just keep doing it.” And I’m like, “Great! Because I like doing it.” So that works out really well. Let’s do that.

ROOM: Do you find it restricting to be labelled as a young adult writer?

MARIKO: Yes and no. I think that there are a couple of mediums I work in where you could say well, because of this this and this, it’s this. Because it’s comic books, it can only be for people who like comic books. There is this limited scope on what is possible within a certain genre.

I was talking to someone recently who was like, “I can’t read YA. It’s not well written.” And I was like “That’s definitely not true.” First of all, I write YA. And second of all, it’s like saying all mystery novels can’t be funny. I think it’s a marketing miscommunication—the idea that because something is for one audience, it’s not for somebody else. Some of the coolest books I’ve read in a long time have been YA books. I’m a huge fan of Patrick Ness and I think that he is writing thrillers. It’s about a boy, but there are greater lessons there. I think it’s a bummer that people are not going to read something because they assume it’s for somebody else.

— Mariko Tamaki

ROOM: But also your graphic novels have clearly “transcended” the label, considering the reach of your audience.

JILLIAN: The books I do with Mariko, we never set out to hit a demographic. They sort of categorize it for us. There’s nothing in the process of making it where we are like, “is this appropriate for a kid this age? We should take this out! Oh dear can we do that?” I think kids want a little bit of titillation anyway. I like it when different people of different ages can read a book and can get something out of it. I just want to make a book that I want to read, to be honest. I know that sounds really pie in the sky. And you’re not making enough money to do it and put yourself through that much pain. Comics are just so painful to make to not be doing what you want.

ROOM: What did you do during your free time as a teenager?

JILLIAN: I actually didn’t draw that much when I was a teenager. I was a horse kid, and that was my life. I feel like I was a very serious teenager. I had a few very good friends but I didn’t really experience teenage life in a normal way. Every free moment was spent at the barn; I took it really, really seriously. I feel like a lot of things I learned from being in that world—training horses, teaching little kids at summer camps, and stuff like that—really primed me and formed who I am as a person and my attitude about work and dedicating yourself to something and trying to do it right, trying to build a strong foundation and not relying on shortcuts. I have always liked making things. I started making quilts in high school, I made zines but I was so dumb I didn’t even know to photocopy them, I just gave them away to somebody. Also, I always really liked journalling, making collages and stuff, not necessarily drawing, but I’ve always really liked working with my hands.

MARIKO: I didn’t do much, I played the clarinet, that took up some of my time. As a teenager, I was somebody who always had a weird craft project on the go, like stone carving or something like that. I was really into watching TV and movies, collages, and small crafty things. I think [making collages] was a very sensory thing. Magazines were like everything when I was a teenager, you would go out and buy a bunch of magazines. I had a friend who collected all the Absolut Vodka ads. That was what you visually absorbed. When I was a teenager, I was also obsessed with the idea that I would read all of the great Canadian novelists. I read all of Timothy Findley, Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, and Margaret Laurence. And Douglas Coupland, obviously. He was like the new guy when I was a teenager, he was the guy who was coming in and doing great Canadian literature but in this way that felt very American almost. He’s very pop culture-absorbed. Basically, I made it my mission in life to read it all.

ROOM: Have you accomplished that?

MARIKO: When I was younger, I was really obsessed with the idea—which is false—that American literature was somehow held as being better than Canadian literature, so I was like No American literature for me. I was a really intense kid. Once I got into university, it kind of changed, I became obsessed with Jeanette Winterson, a lot of great British writers. Now I’m super into Lorrie Moore. My strongest obsession is with long-form journalism and creative non-fiction. If I had to do something else, I would really love to do journalism of some kind. I think it’s the saving grace of any culture. It’s an ability to look in-depth at what’s going on, and the stories that reflect parts of what’s going on in a culture at any given time.

ROOM: Jillian, could you tell me about SuperMutant Magic Academy, your new book based on your web comic?

JILLIAN: I was sort of thinking about superheroes and how they might spend fifteen minutes saving somebody a day, but what’s the rest of their day like? I started putting little comics together—again with no ambition—but I wanted to learn how to cartoon better. I got bored of my sketch blog and I wanted to do something different that was fast, and easy. So that was in 2010; it’s kind of a really dumb concept—half Harry Potter, and half X-Men, but it’s more Degrassi. It is now compiled into a book, and there’s a longer story at the end of the book that kind of ties it up as well.

JILLIAN: I was sort of thinking about superheroes and how they might spend fifteen minutes saving somebody a day, but what’s the rest of their day like? I started putting little comics together—again with no ambition—but I wanted to learn how to cartoon better. I got bored of my sketch blog and I wanted to do something different that was fast, and easy. So that was in 2010; it’s kind of a really dumb concept—half Harry Potter, and half X-Men, but it’s more Degrassi. It is now compiled into a book, and there’s a longer story at the end of the book that kind of ties it up as well.

ROOM: What else is next for you?

JILLIAN: I’m doing a book with my friend Ryan Sands, who has a publishing company called Youth in Decline, and some stuff I can’t talk about yet. It’s very weird and exciting because you don’t really have control over who has an idea for your work and where people think your work can apply; I think that’s kind of the best. I wouldn’t even dream of doing some of the stuff I do. I wanted to make a comic, but I never really thought that I would be a graphic novelist. I’m just sort of following the breadcrumbs.

MARIKO: I’m finishing the edits of a book called Saving Montgomery Sole. It is about a girl who is kind of a square peg living in a small town in California. She has two moms, and she is kind of the only person like that in her school. In addition to that, she’s obsessed with searching unexplained mysteries and phenomenons online, like seances, ghosts, and stuff of that nature. It’s about her experience with some paranormal type stuff, and also her experience—the equally paranormal experience—of what it means to be incredibly different in the world around you. It’s also about being at risk in some ways. I wanted to look at bullying in a less obvious way, less about the bigger story of getting beaten around at school, and more about the experience of just knowing or feeling you are not welcomed in the place you live. After this book, I’ll start on another book, and then I have another comic book that I’ll be working on. I hope to get these two other things finished over the next two years. And then, I would really love to do another movie. I did a short movie with a friend a little while ago, Happy 16th Birthday Kevin.

ROOM: Can I be presumptuous here and assume a third collaboration is in the works?

JILLIAN: I really cherish the books we have made. I don’t feel that they are the best books we are going to make together, and so that’s sort of the challenge. I feel like we [will] have more books as we grow older together. We sort of play off each other in a way that I will never be able to do myself. There will be another book at some point.

MARIKO: The greatest thing about this working relationship is that we’ve never tied ourselves into deadlines or commitments. I think that both of us really like working together. So for that, I think that we will have to see. The other thing is that it’s an intense commitment to do something like this. I also think that Jillian is a great writer, like she could do her own book. I’m a big enough fan that I really want to see what she would do on her own as well. I think that’ll be super awesome.