From issue 37.2: an interview with Ottawa-based poet Sandra Ridley on her new book, working with the archive, and how place creates atmosphere.

Sandra Ridley is an Ottawa-based poet originally from the Prairies. Her first collection of poetry, Fallout, won the 2010 Saskatchewan Book Award for publishing and the Alfred G. Bailey Prize. Her second book, Post-Apothecary, was short-listed for the 2012 ReLit and Archibald Lampman Awards. Her most recent collection, The Counting House, was published in 2013 by BookThug.

ROOM: What drew you to write in the ghazal form for your Lift poems?

SR: I had been reading ghazals written by Phyllis Webb, Adrienne Rich, and John Thompson. Theirs is beautiful work and that’s what initially drew me in. Ghazals address love, with an element of longing. They can be a lament for a love that is unrequited or lost, or for the forbidden or illicit. They also represent spiritual devotion. Approaching the form slantwise, I abandoned the traditional Urdu and Persian elements of clear rhyme and metre and wrote a sequence of twelve poems for lost filial love, a sisterly love that can’t be returned. I dedicated Lift to my mother’s first-born daughter who died from leukemia just before her second birthday, in the late 1950s, long before I was born.

Part of the tradition involves the poet signing off in the final couplet, revealing their identity by referring to their own name, often in a codified way. The poet provides a signature. Instead of referring to myself, I used the refrain “Dear C.” as though writing letters that would never be received, identifying (by initial) the intended recipient rather than the sender. These were poems I felt I shouldn’t be writing and so it was important for me to keep this secretive element of the form. Now that I’m considering it, I was drawn to the ghazal, in part, because it’s built with a clandestine approach—I didn’t feel comfortable writing about my sister’s death. This story wasn’t mine and I needed a codified form of telling, more than a confessional lyric might provide.

The ghazal is a non-linear, unfolding poem. It’s up to the reader to make associative links between couplets and among the grouped poems. Part of the beauty of the ghazal is that each couplet functions as an autonomous poem. If there is a larger narrative, it surfaces by imagistic echoes. There’s no direct telling.

ROOM: In your latest book The Counting House, the poem “Lax Tabulation” is in response to art by Michèle Provost. Can you talk a bit about how you approached this ekphrasis poem?

SR: The poem responds to Michèle’s art installation, ABSTrACTS/RéSuMÉS: An Exercise in Poetry, exhibited at the Ottawa Art Gallery in 2010. She invited a number of Ottawa writers to participate and our work was presented at Saw Gallery in coordination with Max Middle’s AB Series. Her installation was a reaction to curatorial essays found in high art magazines. Michèle’s ABSTrACTs seemed to me to be akin to plunderverse. With a critical eye, she appropriated text to create Dadaist, visual, and sound-based art.

Michèle sent the writers a twelve-page list of words excised from these art magazines. From this wordlist, we wrote poetic responses. Mine came through a filter of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, and interpretations of nursery rhymes sourced at the Roud Folk Song Index: a compendium of about 200,000 references to 25,000 rhymes, folk songs, ballads, etc. … from the oral tradition. These texts appeared inherently connected and I wondered about what kind of poetry could come from a melding together of their ideas.

ROOM: So you didn’t see the physical artwork until you got to the Ottawa Art Gallery after writing your poems?

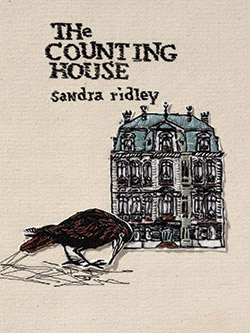

SR: Actually, no. Walking into the Ottawa Art Gallery and seeing Michèle’s art was like walking into a surprise birthday party. Her installation involved paper-based work, embroidery/hand-stitching, and digital media. The poets read their work later that night. As a group, we also performed one multivoiced sound-based piece written by jwcurry. Michèle had given us her primary text, her compiled wordlist, which was the identical material she had worked with to create her own art. None of us had any idea of what the other’s final presentation would be—textually, aurally, visually. Michèle’s invitation to be a part of the process was a generative gift. The Counting House might not have been written without it. And I’m  grateful for the hand-stitched artwork she created, which is represented on the book’s cover.

grateful for the hand-stitched artwork she created, which is represented on the book’s cover.

ROOM: In The Counting House there is a visual departure from your previous work, especially in poems like “Lax Tabulation,” with your use of the space on the page. Could you talk a bit about this?

SR: Content and form influence each other. They work like muscle and bone, and it’s best they’re attached to each other. Also, the page is a space where a poet can score their poem, in aural-visual terms, like sheet music notations, to emphasize breath—be it calm, bated, or more agitated. Visual scoring becomes a tonal guide for the reader. A reader can be drawn to, or pushed away by, the physical shape of a poem, even (very often) at first glance. There’s an instinctive emotional response to how the poem is shaped on the page. In “Lax Tabulation,” the words have a regimented cadence. There are columns and rows. There is breath and bated breath. A silence manifests in the white space, as in any poem.

Another factor I was considering was if I intended this poem to be an accountant’s tabulation or ledger, say if an accountant was tallying the content in a torqued way, what would a balance-sheet poem look like, structurally speaking? It needed to be a sequential poem with columns and rows. And because of that physical format, the text can be read both horizontally and vertically, giving two angles of reading, or two voices/processes of thought. A reader can extrapolate associative links.

I wanted the text to be both flexible and rigid, suggesting open and indefinite meanings. When writing it, I was working through kind of a sudoku poem-puzzle. Math seemed to be involved. I guess, in that, it’s no different than any other poem. Every word is chosen and placed in a particular way that feeling and meaning expands exponentially.

ROOM: I noticed I could choose which direction to read the text …

SR: It worked! I hope that if the text is read from the left side to the right, one type of power dynamic surfaces, and when read from top to bottom, there is a different exchange.

ROOM: Where does public performance fit in with your creative practice?

SR: Readings, actually all public engagements, are distressing for me. I’m introverted and often end up feeling awkward and terrible about multiple aspects of them, though I do see the purposes and benefits of public performance. The writing might connect with someone, and by reading in front of others, I become acutely aware of a poem’s obvious flaws, especially a new, raw poem. This doesn’t happen as often when reading work out loud to myself at home. Reading a raw poem to an audience gives me a chance to address weaknesses before that poem finds a home in print. But I’m rarely courageous enough to read in-progress work. I envy and respect this in others. Reading any material in public gives it life.

ROOM: How did you come to write poetry?

SR: Happenstance? A creative chain reaction? For a few years, I’d been working with photography, developing in black and white. I began adding words to the photos because I thought that the images weren’t conveying enough.This textual overlay became more interesting and this was a pivotal revelation for me. This attitude shift may have come from a conversation I had with Justin Wonnacott, a brilliant photographer and my teacher at the Ottawa School of Art. We’d been talking about intentionality and what can be considered a creative act. As an artist (photographer, writer, or otherwise) are you actively creating something or representing something that’s already been created? What’s your role? How involved do you see yourself? How active or passive? I could take a photo of a street scene and consider that to be a creative act. But that street scene had already existed. I could filter it through a particular frame, my lens, and chosen photochemical processing. Working with words seemed to bring me closer to a source of primary creativity. Sure, our language already exists, but I like to envision the romantic notion of plucking words from the ether and making something new of them. And sure,

experiences associated with them are many and have already happened, but when writing poems, I do feel that I’m more directly active in creating something out of nothing.

ROOM: Your books are usually working through a connected theme. What is your relationship with a project?

SR: I’m not a storyteller, although I adore the novel and short story forms. But I do believe that if my books are read cover to cover, they can work as disjunctive stories, or montage narratives, so there is a contradiction in my thinking. Small moments open large. I approach small packets of time from disparate angles and perspectives, as determined by the content of the book. If you open one moment large, you find depth and breadth through multiple individual pieces, not only within that one first piece that arrived. One poem might be fragmentary. Disparate pieces become tethered through sequences.

ROOM: I read on rob mclennan’s blog a quote from you about your experience jumping a fence to look through the grounds of the abandoned buildings in Fort San, a TB sanitarium in Saskatchewan, to get a real sense of the environment. Is environment exploration a usual part of your writing process?

SR: Getting a sense of the place informing a poem or larger project is a vital part of the process for me. The physical environment shapes a poem. It creates an atmosphere. Each place is a nexus for ecology, history, politics, socio-cultural relations, etc. Nothing exists in isolation. When you start to research or write about one element of a place (or idea), what surfaces is an abundance of connections, or trajectories, regarding content. It also generates new ideas and directions that you wouldn’t have otherwise considered.

Lift had been published by the time I was on the grounds of Fort San. Fallout was about to be released by Hagios Press. I’d been thinking about what my next manuscript might be. Because I work in longer forms, mostly serial, connected poems, I wasn’t waiting for the next individual one to arrive; I was hoping to find another idea that could become a book-length long poem; a concept that could become the backbone for a long sequence. I was drawn to how haunting the sanitarium buildings seemed. What happened behind closed doors there? What had the patients experienced? What had they felt? There was a story, many stories associated, and I could see how there would be enough material to support a full-length book. I was curious about the atmosphere of the place and how that would affect the emotional state of those who had been treated there. Healing therapies were (and often still are) painful, dehumanizing procedures. Being on the grounds gave me a sense of deep isolation and that became the entry point for Post-Apothecary.

Also, I find that each space or idea has its own resident language—a word-hoard outside of the vernacular. Once you start looking deeper, researching the space, you find terms like “blood-let,” “collywobbles,” and “wormwood.” Exploring the sanitarium as a space brought with it the implications of treatments for tuberculosis and mental illness. There was remarkable poetic material for me to work with.

ROOM: Besides going to a location and exploring a space visually, do you research at the archives?

SR: For Post-Apothecary, I did. I’m lucky to be living in Ottawa because I have easy access and close proximity to Library and Archives Canada. I lived there for much of one winter.

ROOM: Did you do most of the research for Post-Apothecary in Ottawa?

SR: Yes. Post-Apothecary isn’t specifically rooted to one place—it’s about a feeling that could be found anywhere. I did spend time at the archival museum of Saskatchewan Hospital, a long-term stay psychiatric institution in North Battleford. I found treatment-related information: medical research reports, admittance forms, physician notes, patient letters home, and permissible activity plan pamphlets (i.e., “What you can and you cannot do with your day”). Their archives also house documents on LSD therapy, instruments for lobotomies, as well as one of Canada’s first electroshock therapy machines. I was also given a private tour by the facility groundskeeper and longest employee, Bill Pooke. He had countless stories. He took me to a site, overlooking the North Saskatchewan River, which contains several hundred nameless, numbered graves.

ROOM: Many of your books have a connection to the Prairies. How does place affect your writing?

SR: For me, place is atmosphere. Fallout is intimately connected to the Prairies. It’s about the experiences of an isolated family living on a farm in the 1950s. That sense of inherent removal and remoteness had to be directly addressed. I think a writer is also affected by indirect connections to place. All of us are. We’re affected not just by geographical bioregion or urban locale, but also by more proximal, intimate surroundings, like a hospital room without a window. One’s place is external and internal. What mood does physical space create?

State of mind and spirit come largely from our environment. Our identity is shaped by where we are. I’m thinking of the emotional landscape. What does isolation feel like in the body? What about joy? How can emotions, or internal atmospheres, manifest on the page? How does emotional content influence form? These are questions that I consider when thinking about how place, or atmosphere, affects my writing.

ROOM: Just picking up on what you’re saying about removal and remoteness, when I’m reading your work I do feel that isolation, whether through the atmosphere you create or the space on the page, and I’m wondering if this is part of an overarching question you are working through?

SR: I think it might be true that writers and artists are trying to answer one question over and over again through their work, as though there is one primal concern (or idea or image) for each individual creator, which becomes a persistent source of material or a consistent way of approach. It’s the one element that they keep returning to and circling with all of their works. Maybe it’s the end-point. It’s a process of which we might not be conscious. Maybe that’s what you are sensing? It may be that I’m circling these senses of isolation, dislocation, aloneness, constraint, and restraint—and the existential crisis that comes.

One of the epiphanies I’ve had as a writer was that my poems didn’t have to be about me. So while personal connection to place does play a role, a poet doesn’t have to be limited by what they’ve lived. This creates an interesting dynamic for some readers who may feel that a writer is writing purely about themselves. Poetry can be fiction in a different form.

ROOM: Post-Apothecary looks at illness and trauma. Similarly, I recently read a great book by Toronto poet Erin Knight called Chaser; she was exploring illness and diagnosis as well. Why do you think writing about women and diagnosis still resonates so loudly with writers today, many years after a work like “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman was published?

SR: Great question; a thesis question! Erin Knight’s Chaser is a remarkable book, and I love, too, your reference to “The Yellow Wallpaper.” It’s one of a few small works of fiction that I remember reading from university days. It was a pivotal text for me, as was Susan Griffin’s Woman and Nature and R.D. Laing’s The Bird of Paradise. “The Yellow Wallpaper” could very well be part of the unconscious foundation of Post-Apothecary. It’s a feminist text examining repression and freedom, power relations, and assertion of voice (as the hidden, the surfacing, and the manifest). It also looks at connections between states of body, spirit, and mind. I suppose that as long as there’s an “Other,” this kind of writing will be necessary and will resonate.

ROOM: Final question—what are you reading these days?

SR: I’ve arrived a couple of years late to Emma Donoghue’s Room, a story about a boy and his mother trapped in a small room. It seems I’m still considering how isolation affects emotional state. Alongside Room, I’ve also been reading Stephen Hawking’s The Grand Design and Oppenheimer’s The Flying Trapeze: Three Crises for Physicists. Both of these were gifts. I keep coming back to non-fiction. I’m curious about any subject that I’m not familiar with. I feel like I know less and less and so the spectrum gets wider and wider. When ideas excite me, I feel like I’m learning something—and this can bring me back to my empty page. These days, my guilty pleasure isn’t reading. I’m smitten with “Coast to Coast AM,” a late night paranormal- and conspiracy-themed syndicated radio show that unites scientists, long-haul truckers, and shortwave enthusiasts like me with some of the most unbelievable (believable?) theorizing around.

**Photo Credit: John W. MacDonald

Originally published in Room 37.2 Expanding the Voice.