Before reading this essay about accessing appropriate health and wellness care as a sex worker I’m going to ask you to reflect on your own relationship to othering—perpetuating, witnessing and surviving it—and how it has impacted your health.

1. Trust Exercise

One upon a time … in fact, I’m referencing 1996, but maybe the familiarity of a faerie tale intro will thwart the standard dubiety or “othering” that occurs when a sex worker speaks up. Othering is the means in which sex workers are rendered into makeshift statistics within countless shelved reports. Othering is how sex workers’ voices are dismissed as the most current legislation governing prostitution is being passed (C 36 in Canada, for example). Moreover othering is an everyday mindset that pervasively allows negative perceptions of sex workers be openly asserted, as in: we are heteronormative family wreckers, criminals, disease spreaders, drains on the system, victims, and patriarchy perpetuators.

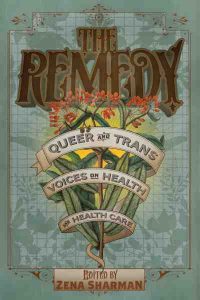

Before reading this essay about accessing appropriate health and wellness care as a sex worker I’m going to ask you to reflect on your own relationship to othering—perpetuating, witnessing and surviving it—and how it has impacted your health. You’re reading The Remedy, and if I take this as a clue, I can imagine that aspects of your own identity have been ousted by the dominant mainstream, and maybe othering has literally sickened you.

Solidarity work is much more complicated than “we’re all in fight this together” kind of thinking, of course. I’d like to share some personal and practical knowledge that I’ve learned about how solidarize with sex workers. And sex workers need close allies. Not “for the sake of the argument” close or “save the less fortunate” close, but “eye-to-eye” close. To encourage this closeness, I will invite you to participate in self-reflection, seek-and-find games, holistic intervention, and yes, I’ll use faerie tale phrasing … Once upon a time, in 1996, a family physician was seeing a patient for the first time. This patient disclosed that she was violently raped by a bad date while working on the street and since then she’s had difficulty managing back and leg pain, sleeping, eating and concentrating. This patient said, “I’ve only had shitty experiences with doctors. What can you tell me that will help me trust you?”

Now imagine you are that family physician or that nurse, that social worker, that clinical supervisor, health care researcher, emergency room receptionist, front line shelter worker, crisis line volunteer, that academic advisor, that confidant or lover or friend. What would you say to help build trust?

And indeed trust has been broken. I am not the only sex worker who has waited anxiously in a doctor’s office while brooding over scores of “shitty” previous experiences. A 2014 survey—the Street Based Sex Worker Needs Assessment— lead by a research team of former sex workers in Toronto, Barrie and Oshawa, showed that a quarter of the interviewees almost never see a health care provider, while nearly half rarely or never disclose their involvement in sex work to their health care provider. Judgmental health care and social service providers were the most prominent concern mentioned by interviewees.

This is painfully similar to a 2005 survey—the Social Determinants of Health Care Access Among Sex Industry Workers in Canada—conducted in cities within British Columbia where many sex workers reported feeling intimidated and shamed by health care professionals, and choose to withhold information relevant to their health care due to fear of discrimination. Similar again to a discussion paper—Addressing Sex Workers’ Risk for HIV/AIDS—presented at the 1996 International Conference on AIDS, which examined how sex workers have historically been disinclined to access health and social services on account of the stigma associated with their occupation

I’ve gathered countless testimonials myself, not as a researcher, but as a co-worker and friend. There was the parlour worker who teared up in the staff room as she recounted a recent STI test where the nurse startled her by attempting to insert a swab up her anus before she had finished taking down her pants. The escort whose examination was interrupted by a half dozen medical students, none of whom greeted her, used her name, or acknowledged that she could hear them while they discussed her profession and diagnosis. The street worker who warned me about a particular receptionist at the free clinic—a receptionist that had said, “You people are always sick,” and made her wait indefinitely without giving her an appointment number. And there is me; the “shitty” experience I remember most clearly is being told by a hospital psychiatrist that “the human spirit can only take so much” and “if I continued down my path, there would be no recovery.”

Once upon a time in 1996, that family physician addressed my question about trust by saying, “I believe you. I’m sorry this happened to you. With your permission, I’d like to run some physical exams …”

2. (Make) Believe

We are fourteen women gathered around a conference table to train as volunteers at an anti-violence feminist crisis line. Together we are brainstorming how to respond when a caller discloses rape or violence. ‘I believe you’ is written in black sharpie on flip chart paper. ‘I believe you’ has likely been written on flip charts by anti-violence feminists for decades. ‘I believe you’ is the first step in countervailing victim-blaming and social scrutiny of survivor’s stories. It is a non-judgmental pre-cursor to active listening, offering resources and supporting the survivor’s choices for healing. I am grateful to the feminist who taught me to believe.

My gratitude is tainted, however, by the number of times I’ve been forced to defend my commitment to the anti-violence work to abolitionist feminists—who intentionally confuse sex work with trafficking and violence against women. Abolitionists who aim to keep (or make) sex work illegal, and further still who propose to see sex work no longer exist in any form. This is a both ludicrous—as sex work will always exist—and glaringly paternalistic and condescending towards sex workers’ individual and community autonomy.

The abolitionist argument alone is exhausting enough, but the real damage occurs when abolitionist feminists staff support services that sex workers may need. For example, I have witnessed a white feminist front line worker tell an Asian sex worker that she could stay at the emergency women’s shelter as long as she recognized that sex work isn’t work, it should never be called work, only abuse.

Would you want to access a support service where a fundamental part of your lived experience was discredited at the front door? “I believe you” has a beginning and an end. Too often sex workers are not believed—and we are not believed by the very services and organizations that claim to uphold the phrase “I believe you.”

3. Seek-and-Find

The workers’ compensation board in British Columbia and I have something in common: a fondness for seek-and-find pictures. My favourite page of WorksafeBC.com is “What’s wrong with this photo?” where you can seek-and-find hazards in various occupational scenarios. For example, a photo of a landscaping scenario shows one worker wearing flip-flops while pushing a lawn mower and another appears to be texting while climbing a ladder. This is observational learning.

Sex workers are excellent observational learners, however, I have yet to discover a “What’s wrong with this photo?” of a sex workplace scenario. Let’s create one now. I’ll give you a scenario—a real and personal account—and you try to find the risks and the harm-reduction activities. Ready?

A client waits for me in the massage room. I haven’t seen him before although he is a frequent regular at the parlour. As I grab my trick bag of condoms, water-based lube and alcohol-free disinfecting wipes a co-worker informs me this client uses cocaine. “Beware of coke dick,” are her exact words. In the massage room the client has set up a few lines of coke on the night stand beside the money he’s set out for my tip. Normally, I collect my tips quietly, but as the client offers me his coke straw I roll up a bill and say, “I’ve always fantasized about snorting coke through a hundred dollar bill.” Minutes later we are naked and covered in massage oil. The client repeatedly squirts oil from the bottle onto my breasts and we both laugh like this is the funniest thing to ever happen. In my mind, I curse the recent trend in “oiled up” porn (fucking oil!). I slide my body over his, being careful, though not as careful as I could be, of any pre-cum leaking from his limp penis. When he gets an erection, he grabbles eagerly for a condom. “Let me do that, baby,” I say. I stick my ass in his face, talk dirty to him and play with his balls as I hastily wipe some oil off my hands and get a condom on him. His groans and pounds his fists on the wall in frustration as his erection wavers.

How many did you find? You could find up to fifteen depending on how you tally up risk and safety. Condoms and water-based lube are easy to spot. Alcohol-free wipes are included as safer sex supplies because isopropyl alcohol weakens condoms, as does massage oil. There is a low risk of Hep C infection from sharing coke straws. There are lower concentrations of HIV in pre-cum than in semen. Even Dr. Google will give you this information. What may be less seek-and-findable is the immeasurable safety of working together. In this scenario, I am with other workers inside a parlour where we can exchange information about clients. How would the risks increase if I were alone and high with a new client who was growing frustrated?

Sex workers are excellent observational learners not just because our occupation requires us to be hyper attentive to what’s happening around us, but also because ultimately we depend on each other to model safer work practices. Criminalization, full or asymmetrical, and other systemic barriers that prevent sex workers from working together and freely sharing information amongst ourselves puts our health at risk. It not only impedes on our ability to learn from each other, it increases likelihood that police will refuse to protect sex workers, and instead will routinely confiscate condoms from street and massage parlour workers as evidence of criminal activity. Indeed, this is already happening. It means that outreach services, like mobile health vans, will face more barriers getting safer sex and harm reduction supplies to sex workers that need them. Criminalization fractures sex workers from each other and from appropriate health services. I will say it here, and likely countless times in the future, if you want to be an ally then support decriminalization.

There are several sex worker led organizations that provide information about decriminalization and sex work justice. A few from coast to coast include: PEERS Victoria, PACE Vancouver, Maggie’s Toronto, Big Susie’s Hamilton, Power Ottawa, Stella Montreal, Stepping Stones Halifax. Friends in the USA and internationally, the Bay Area Sex Worker Advocacy Network (BaySwan) keeps an excellent list of organizations on their website. And from any location, Tits and Sass, a group blog run by sex workers, is my absolute favourite online read.

Supporting decriminalization can take many forms. You might host a potluck fundraiser or dance party to raise some donation money for an organization. Invite some friends over for a write-in and write letters to local senators or government officials, or co-author an op-ed to your local paper or political blog. Why not volunteer (contribute to the cause and also you might meet cute workers or allies)? Share petitions and information on social media. Become so darn articulate that you could readily speak up for sex workers rights within your own communities? Be an outspoken, bad-ass, sex worker ally at an upcoming dinner party—try it!

4. Holistic Intervention

In a land far far away … in fact, I’m referencing a recent queer dance party held in a warehouse located along one of Vancouver’s last street working strolls. Like any queer dance party, a good number of the party-goers, myself included, were hanging around outside to air our sweaty bodies or smoke or flirt with sweaty smokers. A gorgeous queen in daisy dukes sauntered over to the curb and pretended to hustle; her friends hooted at her. My chest tightened. This party was located six and a half blocks from where I was violently raped by a bad date.

Some femme shouted, “No honey, you are way prettier than the hookers around here.” My temples began to ring. Three blocks away was where Sheila Catherine Egan was last seen. One block away was where Jennie Furminger was last seen. I remember their names because I remember them. Sheila was two years younger than me. Jennie was born and raised in my hometown. Is this how they shall be spoken of—as “ugly hookers”—by queer kids stopping by the stroll for a cheap place to drink and dance?

“Don’t you ever insult the women in this neighbourhood,” I raised my voice.

Everyone around me froze. The femme eyed her friends pleadingly like she was looking for back up. “It was just a joke,” she said.

I lay into her again, “Don’t you ever—”

No blood test can detect grief or disgrace. No research survey can quantify the harmful impact of having your queer communities—your so-called safe, inclusive spaces—other you again and again. To be othered by anti-sex worker comments or “jokes” stings, certainly. What cuts deeper is the othering of having no one stand beside you. No one offered a single word of solidarity in that moment—and that moment is by no means a unique example. At times, this has caused me to see other queers as potential threats to my dignity and wellbeing, and it has also caused me to isolate from queer communities altogether.

There are always ways to intervene against othering. When I say “intervention” I’m not talking about those pop-sensational reality shows about addiction, I’m talking about holistic and preventative care. The healing properties of allyship also cannot be measured by medical assessment, but they are equally real. And we must believe we can heal from the sickness and damage. Staging an intervention against othering requires some planning. The greatest care an ally may offer is simply to be ready to speak up and stand with sex workers. I offer the following examples:

A friend calls me the day before the International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers and asks if I’d like her to march in the red umbrella procession with me, and should she call other friends so I have an ally posse.

A professor in the creative writing program where I now work performs a pro-decriminalization themed Tedx Talk called The red umbrella — sex work, stigma, & the law, and forwards the YouTube link to all of our colleagues. I sit in my cubicle with awe as I read thoughtful and affirming replies come in from nearly every professor and staff member. Being “out” at work becomes more secure in a matter of hours.

A friend joins me each year to host a fundraiser cabaret for the Missing and Murdered Women’s March. Together we gather a group of queer artists who volunteer their time and talent to raise money for the Aboriginal and community elders and families of the missing and murdered women in Vancouver. Sometimes I keep the donation money in my bra before delivering it to the elders—just for old times’ sake.

My wife takes the morning off work to go to a sensitive doctor’s visit with me. She says, “I can wait in the lobby or come into the exam room?” and “I can help you vocalize your concerns to the doctor or I can support you quietly?” and “Afterwards, can I take you to that fried chicken place you like?” and she says, “I love you. I’m with you.”

And that family physician from once upon a time in 1996 happens to be a lesbian. After years her clinical practice, she moved into a different field of care. Though, I still see her from time to time at queer events. She greets me with professional discretion, yet also undeniable warmth. I will forever remember her saying “I believe you.”

And right now, you are reading my words. I thank you for your kind attention and your solidarity. Never forget that you too can do this healing work.

This essay was originally published in

This essay was originally published in